According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), over the past two years, one in five insured adults had an unexpected medical bill from an out-of-network provider. In emergency departments across the country, 18% of visits result in at least one surprise bill, but rates vary by state. When insurers don’t cover the cost of out-of-network care, the patient is “balance billed” the difference between the total cost of services being charged and the amount the insurer pays. As a result of these practices, two-thirds of adults overall are worried about affording unexpected medical bills for themselves and their families.

That fear is very real, considering that most families do not have enough money saved for a simple emergency, let alone thousands of dollars in unexpected medical costs. According to the Federal Reserve’s 2018 report on the economic well-being of U.S. households, consumers faced with a surprise medical bill generally pay $600 or more, as surprise bills often come in at a rate 600% higher than if the same care had been billed under Medicare.

The following year in 2019, the Federal Reserve also reported that 40% of American adults would not be able to cover a $400 emergency with cash, savings, or a credit card charge that they could quickly pay off. They went on to note that about 20% of those surveyed would need to borrow the money or sell something to come up with the $400 and an additional 12% would not be able to cover it all. View fullsize

For patients, getting an unexpected bill for health care can be financially devastating. Individuals with high deductibles and those who have an emergency where they are not able to select the provider are those more likely to experience surprise medical bills.

SO WHY DO THESE SURPRISE BILLS THAT ARE SO DETRIMENTAL TO PATIENTS’ FINANCIAL WELL-BEING HAPPEN AND HOW DO WE AFFECT CHANGE?

In 2018, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago reported that 57% of Americans surveyed had been surprised by a medical bill that they had assumed was covered by their insurance. Of those who received a surprise medical bill, 20% were related to the medical provider being outside their insurance carrier’s provider network.

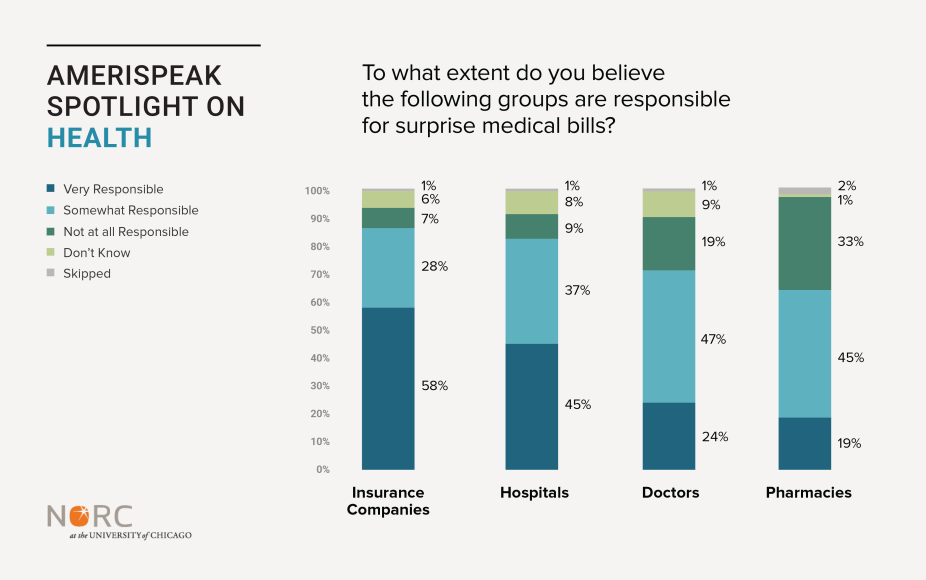

The public holds insurers and hospitals most accountable for surprise medical bills. Politically speaking, majorities of both Democrats and Republicans are in support of government action to protect patients against these surprise bills.

While lawmakers in both parties appear unified on solving the problem, that is largely where the agreement ends. Fixing this particular problem is ultimately a fight between doctors and insurers over rate-setting and reimbursement. Until there can be an agreement between those two parties on a fix, legislators are being continually pressured to enact changes that will protect patients. While a variety of bills have been introduced to address surprise medical bills, none have been enacted.

In absence of Congressional action, the Trump administration put forth its own solution that places the onus squarely on hospitals: The Executive Order (EO) on Improving Price and Quality Transparency in American Healthcare to Put Patients First.

Signed by the President on June 24, 2019, the EO directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to require hospitals, “…to publicly post standard charge information, including charges and information based on negotiated rates and for common or shoppable items and services, in an easy-to-understand, consumer-friendly, and machine-readable format using consensus-based data standards that will meaningfully inform patients’ decision making and allow patients to compare prices across hospitals. The HHS regulation should also require hospitals to regularly update the posted information and establish a monitoring mechanism for the Secretary to ensure compliance with the posting requirement, as needed.”

On November 15, 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued final policies regarding the hospital price transparency requirements and cited January 1, 2021, as the date by which CMS expected hospitals to come into compliance with the rule. CMS expects hospitals to provide something akin to the chart below for health care consumers to access:

CMS requires that hospitals display the minimum and maximum negotiated charges as well as discounted cash prices for a minimum of “at least 300 shoppable services, including 70 CMS-specified shoppable services and 230 hospital-selected shoppable services.” If a hospital does not provide 300 or more services, they are required to list every service they do provide and they must be treatment and/or services with which patients are commonly provided.

Under Section 2718(e) of the Public Health Services Act, CMS is authorized to monitor compliance with the rule, auditing hospital websites, and determining if the requirements have been met. CMS may require hospitals to submit corrective action plans and can impose monetary penalties not to exceed $300 per day out of compliance. The penalty is based, according to 45 CFR Subchapter E, on what CMS determines the effective date for the violation(s) to be.

In December 2019, the American Hospital Association (AHA) filed a lawsuit against CMS arguing that the final rule is not within CMS’s statutory authority to issue or enforce. On June 23, 2020, a federal judge upheld the rule, determining it to be, “legal under sections 2718(e) and section 2718(b)(3) of the Public Health Service Act and section 1102(a) of the Social Security Act.” The judge also dismissed the lawsuit’s claims that the final rule violates the First Amendment and will create confusion among consumers. AHA immediately filed an appeal (June 24, 2020) and urged CMS to delay implementation of the rule given the COVID-19 crisis and the pressure under which the hospital systems across the nation are currently operating.

WHAT COULD THIS RULE MEAN FOR THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM?

CMS’ regulations rely on a market-based approach which suggests that armed with information, consumers will be able to make informed decisions based on price and quality, therefore reducing the occurrence of surprise medical bills. And while this may be true in many product and service sectors, the health care system does not always follow traditional rules of consumer economics.

And as with any change to health care, there will be impacts to other stakeholders in the system which may or may not move the system further down the path of achieving the Triple Aim (improved health, improved care, and lower costs). HealthAffairs recently cited ten short-term consequences of the Executive Order on Improving Price and Quality Transparency, including:

- Prices for some hospital services will become more competitive;

- Prices will increase for other hospital services;

- Some regions may see higher prices overall;

- The new dynamic of negotiation will accelerate consolidation;

- Some rural and safety-net hospitals will not be able to survive;

- Adoption of new technology will slow unless it has a very strong value proposition;

- Payers will experiment with new benefit designs and reimbursement models;

- Price transparency will add a new dimension to antitrust compliance;

- The rule will not affect the majority of consumers, who are insulated from the true cost of health care; and,

- The rule could complicate efforts to advance value-based payments.

Of all of these consequences, the last may be the most impactful in the long run. For many years now, the United States has attempted to reform the inefficient fee-for-service payment model and move towards paying for value, thereby creating a system that promotes whole-person health and emphasizes prevention and wellness.

As HealthAffairs notes in the previously cited article, the fix for pricing transparency is based on the assumption that payment is provided on a fee-for-service basis, aligned with the traditional “volume-based” revenue strategy. Requiring a focus on this payment structure does not allow hospitals to put resources towards furthering alternative payment methodologies and value-based care.

Additionally, the transparency rules may cause hospitals to become more risk-averse which could lead to a slowing of the addition of important technological advances in the delivery of health care. This ultimately impacts the provider’s ability to deliver health care to some of the country’s most at-risk populations. Telemedicine, telehealth, telepsychiatry, and many other virtual services provide care to individuals who, for various reasons, would not or could not access care otherwise. Providers that are too burdened by the impact of the transparency rules may forgo the development of important virtual services and, thereby, fail to adequately serve at-risk populations who are unable to appear for in-person treatment and services.

What could this new rule mean for consumers?

Transparency is important for consumers and surprise medical billing is a disaster for many American families. For consumers seeking elective surgeries, pricing availability in advance of the event is a boon. Those seeking to compare prices between practitioners for services not covered by insurance will be able to find the information easily online. However, Americans covered by insurance may find it more meaningful and informative to contact their insurer for pricing details in advance of treatment and services.

MedData reports that:

- “75% of patients are looking up the cost of medical procedures online.

- 63% of patients said knowing their out-of-pocket expenses in advance of service impacts the likelihood of pursuing care.

- 49% of patients [indicate] that having clear information on expected out-of-pocket costs before receiving treatment impacts their decision to use a health care provider.”

As such, it would seem that Americans are already looking into the cost of their care without the aid of the Executive Order on Improving Price and Quality Transparency, rendering the need for its existence moot. Further, patients in the midst of a medical emergency will not find themselves in a position to ‘shop around’ for care based on cost and quality.

Ultimately, while this fix may resolve a pain point for some consumers, pricing information alone is not sufficient to move the system towards greater value nor will it meaningfully address the problem of surprise medical bills. This is because pricing is only relevant to consumers when accompanied by quality, safety, and health outcomes data that allow for shared decision-making and meaningful cost conversations between patients and clinicians. Further, patients in the midst of a medical emergency cannot take time to stop and shop around. We must continue to seek and develop solutions in health care that equally address all three goals of the Triple Aim.