So, you’ve decided you want to launch a Capital Campaign to support a large upcoming project for your organization. Once you’ve really defined the purpose of your Capital Campaign and build buy-in across your organization and leadership team, the real work begins to develop a Campaign’s strategic plan to:

- Build your campaign team and excite your Board of Directors

- Conduct a feasibility study and identify next steps to address the findings

- Develop a campaign budget

- Develop a case for support and corresponding campaign materials

- Create a gift chart, assess your current donors’ giving potential, develop a prospect strategy

- Craft a communications plan with two phases: a quiet phase and a public phase

With the right tools for support, you’ll be able to create a roadmap that guides your campaign from start to finish—and beyond.

Building your campaign team and exciting your Board of Directors

First thing’s first. You can’t plan and run a Capital Campaign on your own. You need a team of staff, Board members, supporters, and consultants who are ready to roll up their sleeves and commit to do the work for the long haul to make the project a success. It’s also critical to build this team early to let them weigh into challenges from the outset and get their buy-in early. You will need to identify:

- Campaign chair. We’re not into sports analogies, but if we were, this individual would be the quarterback. Or the center. Or, forget it. The campaign chair is your ultimate champion, moving work through the Capital Campaign committees and serving as the holder of the megaphone in your organization’s work to communicate with the community. In many cases, this is a Board member. In some cases, it is a prominent individual in your community like a business, government, or religious leader.

- Planning committee. Ideally, your planning committee should consist of about 8 to 15 people, including staff, volunteers, existing donors, highly-engaged Board members, and consultants who will work together on the Campaign’s strategic plan (or, put simply, do all the work that must be done between day one and the launch of the campaign during the public phase).

- Steering committee. The steering committee helps run the campaign once it has been launched—and they’ll be tasked in making sure it’s on track and on its way to meeting revenue goals. Typically, this is a subset of the planning committee who have the drive and interest in participating throughout the course of a one, three, or five-year Capital Campaign.

These people are your storytellers who are going to make the case for your organization, the Campaign, and the future state you’re trying to convince people to invest in. They must be people you trust with expertise you value. Once you settle on them and build out both committees, you should assign formal roles as you would for a Board of Directors, including a Vice Chair, Secretary, Finance Chair, Events Chair, and more.

One of the decisions you will also need to make during this part of the process is whether you’ll hire a Capital Campaign consultant, or an expert or team of experts to become an integrated part of your Campaign teams to provide both general support and specific services. Consultants can help keep committees organized and on-task, run Campaign feasibility studies (more on that, below), craft a case for support, or write and execute on your Campaign’s communications plan. Especially if your organization has never run a Capital Campaign before, a consultant can help keep the trains running on time and offer valuable advice and expertise that will save you both time and money in the long run.

Finally, you don’t need to just inform your Board of Directors what you’re planning to do. You need to excite them and get them ready to hit the ground running to support the organization’s work (and fund the campaign itself!) during this highly challenging time. Your Board of Directors should be the sounding board for your campaign messaging – and you should communicate early and often with them about the challenges you’re facing. To get them there, consider special meetings, trips to the site of your future facility or building, or get them involved in the service delivery your organization does every day. When they’re as ready to do this as you are, you know you’re ready to move to the next step.

Conducting a feasibility study

In the last article in this series, you developed a budget for the project you are trying to fund to understand exactly the kind of revenue you need to bring in the door to make your Capital Campaign a success. Here’s where things get tricky: just because youand your organization’s leadership think that a Campaign is the right thing to do, it doesn’t mean your donors do. That’s where a feasibility study comes in—it simply determines whether your grand vision for a Capital Campaign and the money you think you need to raise is viable for your organization right now.

During a feasibility study, an objective third-party interviews key stakeholders and focus groups of current donors, potential donors, and community members about their perceptions of your organization, its work, its potential, and the specific project that you are trying to fund. It is not optional. We repeat: a feasibility study is not optional.

The objective third-party is also critical – a donor is going to be more honest about their thoughts if they’re talking to someone other than a staff member, a Board member, or your President and CEO. Similarly, an internal staff member conducting a feasibility study is more likely to ignore findings that could potentially throw the Capital Campaign into uncertainty – a third party is going to tell you the truth and give you strategies to address what you learned during the study.

The information you obtain during the study can help you steer your project, your messaging, and help you narrow down. Additionally, this study goes a long way to build up (very) early support and awareness from key donors who will be some of the most important people you go back to during the quiet phase of your campaign (more on that below!)—and it shows your donors you value their opinion.

To get ready for the study, you want to have an early, draft version of your case for support to use during the study (this will likely change after the study when you have more information and data to strengthen it) and determine the key stakeholders you’re going to interview as part of the study.

When considering who to include in your feasibility study’s interviews, you want to identify individuals who “walk the walk” for your organization—or, as one article recently put it, “candidates [who] have a strong, genuine connection to your cause and organization. Look to those who are actively involved in your [programs], or who have led past events to success.” Also, “You want a good mix of candidates. Think about those who are incredibly supportive of your nonprofit’s initiatives and those who may be more critical; both can provide valuable insight.”

Consider the following types of key figures:

- Current and former Board members

- Current of former major gifts donors

- Planned gift or legacy donors

- Key volunteers

- Community stakeholders

- Business owners and vendors

- Recipients of your services (patients, parents, alumni, students, etc.)

When it comes to the study itself, you’re aiming to answer a handful of questions:

- Is our current donor base large enough to support our Campaign goal?

- Who are our major gifts prospects and how much can we expect to raise?

- Does the project make sense to our key stakeholders—and what questions or concerns do they have about the project?

Above all else, it’s critical that you take the results of your feasibility study seriously. In our experience, there are typically three likely outcomes: your project is feasible and your donors are ready to write a check; the project is feasible if problems or challenges are addressed; or, the project is not feasible. On the later, while it can be disappointing, it simply means that your organization has work to do before embarking on a Capital Campaign to strengthen the infrastructure necessary to support the project you’d like to embark on.

Implement strategies based on the feasibility study results

A key part of your Capital Campaign’s strategic plan should be strategies and tactics to address what you learned during your feasibility study. The benefit to working with a consultant is that they can help develop a set of next steps that directly address how your organization approaches fundraising for your Capital Campaign, as well as tactics to address any identified challenges.

If your study revealed that your organization is mostly ready to launch a Capital Campaign as planned with a few tweaks, you might consider adjusting your overall goal or timeline. You might also consider new stewardship tactics to better connect with your donors to generate a better relationship and larger gifts. On the other side, if your feasibility study revealed that your organization is not yet ready to embark on a Capital Campaign as planned, you might need to plan a series of smaller campaigns to grow your annual fund first, or, you might need to build out your Development or Marketing/Communications Department to support the kind of work necessary in a Capital Campaign.

Developing a campaign budget

This is usually the most overlooked part of any Capital Campaign – not what you’re seeking to raise, but the amount of money it will take to run and equip your Capital Campaign for success. Lots of nonprofits think that trying to cut corners and, for lack of a better term, go cheap will help them hit bigger fundraising goals for the project itself down the road, but the reality is that your Capital Campaign will be much more successful if you make the necessary investments in expertise and collateral up front.

There are two questions you need to consider when setting the budget for your campaign (usually in consultation with your Campaign consultant): the successes and shortcomings of your past organizational fundraising plan budgets and what other nonprofits are spending on similarly-sized Campaigns. Consider the cost of items like:

- Your Campaign consultant

- Events over the course of the campaign

- Marketing materials such as printed collateral, environmental design for events, videos, a website, and advertising

- Fundraising software or a wealth screening service

- Donor recognition activities/pieces

- Costs or investments associated with keeping other parts of your organization running while more staff is focused on the Capital Campaign

Once you have a budget you think will work, ensure you share it transparently with your organization’s leadership and Board of Directors for buy-in and approval.

Developing a case for support

You may know exactly what you’re raising money for, but until you put it on paper and make the case to donors, you don’t have a case for support. A campaign case statement is never just about a single building, or a single fundable project. It contextualizes the project within the organization’s purpose and vision for the future. It also always must start with the, “why,” or the problem you’re seeking to solve and how the project you’re seeking to fund through the Capital Campaign helps your organization get closer to realizing that vision of the future and its day-to-day mission.

Similarly, while it’s important to have a draft version ready to give to interviewees during your feasibility study to react to, the reality is that a Capital Campaign case statement is a living document and will be refined as you gain more insight and reactions from the people you seek to make the case to.

A case statement should include:

- Why the organization (not the project) are needed (i.e., the problem your organization wakes up to solve every day)

- The organization’s impact to date

- The specific problem that the project seeks to solve

- The benefits of the project and potential impact

- An estimated fundraising goal, project budget, and timeline

Once you have a case statement, it can be used to develop other materials such as brochures, presentations, videos, graphics and ads, all of which are all usually condensed versions of your case statement. Additionally, best practices suggest that you should consider developing a Capital Campaign website that can house materials for prospects to refer to and is set-up to accept online gifts.

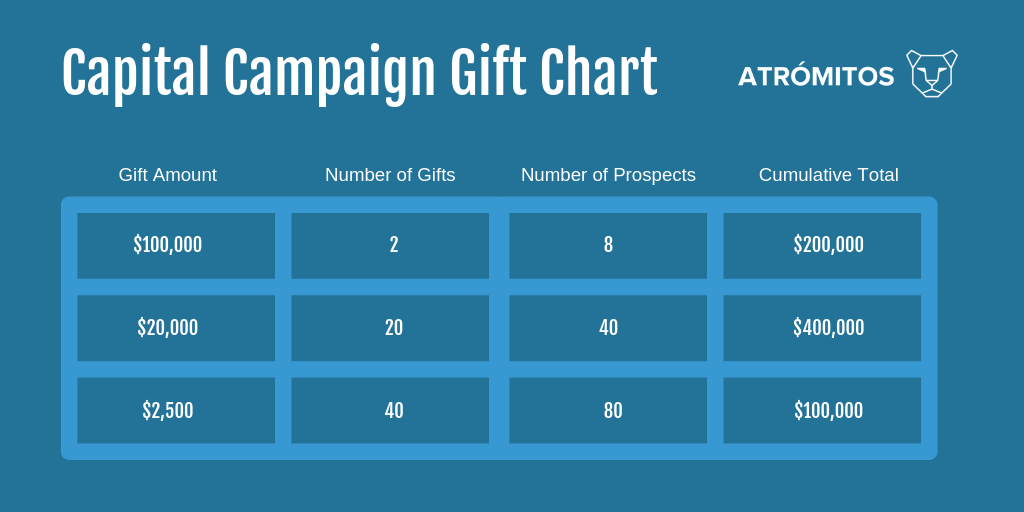

Creating a gift chart & assessing your current donors’ giving potential

A gift range chart is exactly what it sounds like: breaking down your overall Capital Campaign goal into smaller chunks of money you think is possible to secure from donors. In practice, they show your Capital Campaign’s committees, your organization’s Board of Directors and leadership, and prospective donors how you plan to realistically achieve your goal. Your fundraising team will also use the chart to determine how many prospects they need to identify at each giving level to reach the goal of the Capital Campaign.

Best practices suggest that your chart should have a few large gifts that make up 10-20% of your goal, as well as many more smaller giving levels. It’s likely your chart will include many different levels of giving, but here is an example to start from:

Your cumulative total should add up to the total amount you seek to raise for your Capital Campaign. It should also:

- Make a direct correlation between large gifts and a smaller number of donors (i.e., you can only expect a few people to write a large check, whereas you can expect more donors to write smaller checks)

- Include the number of prospects you think you need to identify to secure the number of gifts at each giving level

Your chart will vary depending on how much money you aim to raise, the number of donors you have in your base, and the number of prospects you realistically think that you can identify. To develop a chart that is realistic, you also want to consider a screen for your current donors. Remember: your gift chart is just a guide – not gospel. During conversations with donors and prospects, you may determine potential to seek out a larger gift or even employ a digital small dollar strategy to fund a portion of the campaign through small gifts (smaller than $500) from the community via email or SMS (text messaging) program.

SCREENING YOUR DONOR BASE’S GIVING POTENTIAL AND IDENTIFYING NEW PROSPECTS

Your organization has a donor base that keeps it funded year after year. But the question is: are you maximizing your current donors’ giving potential? The answer is that unless you’ve completed a mass screen for wealth capacity and philanthropic behavior of your donors at every level, you don’t know.

The odds are that you have more than a few donors on your list who could afford to give more – they simply haven’t been asked. The outset of a Capital Campaign is a strategic time to invest in this kind of batch screening so that you can make sure you’re making the best ask of the people who already support your organization and who are primed to give.

You likely already have an annual subscription to a screening tool like DonorSearch—it allows you to research whether a donor has given to other nonprofits, given to political campaigns, and more on an individual level. But an annual or semi-annual batch screening allows you to get that kind of information for a large portion of your donor database without the guess work of who to screen, when. Put simply, this kind of screen can help you identify current donors who are prospects for larger gifts than their giving history with your organization might support.

The reality of a Capital Campaign is also that you’re going to need to identify completely new prospects to reach your goals and prevent donor fatigue—and this is one of the most challenging tasks any fundraiser or organization can undertake.

Where do you start? Your Board of Directors Development or Fundraising Committee.

These individuals—who care deeply about your organization—were picked (hopefully!) because of each person’s commitment to your mission and their networks. You should start by setting up individual phone calls or meeting with each member of this Committee to dig into who in their network might be a potential prospect. From there, build a list of names and complete a wealth screen to more deeply and fully understand who on that list has the potential to become your next big supporter. Then, engage the Committee and your Campaign consultant to build a strategy around making contact with each prospect and developing a relationship.

These strategies could include:

- A meeting with your President and CEO and the Board member they know

- A tour of your facility or in-person look at the service you provide to the community

- An invitation to a networking reception, event, or fundraising gala

Regardless of any prospect’s potential or the number of events and receptions they attend, follow-up is key—and you should assign it to various members of your organization’s leadership team and Board of Directors to ensure that it’s happening. You want to make sure that your organization remains top of mind in the lead-up to making the ask for a major gift to support your Campaign.

Crafting a communications plan with two phases: a quiet phase and a public phase

The final step in your strategic plan to launch a Capital Campaign is to create your communications plan for both the quiet phase and the public phase. Everything from scheduling meetings with your major gifts prospects, receptions, and events to how you plan to talk about your Campaign on social media should be considered and incorporated into the plan.

QUIET PHASE

The quiet phase of your Campaign is critical. “On average, nonprofits raise 50-70% of their goal during the quiet phase of a Campaign.” That means this part of the Campaign requires a communications plan that focuses on and communicates with major donors—in other words, this isn’t the time for an innovative social media strategy, but rather a plan for in-person meetings and small receptions. You’ll want to ensure you have the right materials to put in front of a prospect and the right events and opportunities to keep them engaged in the lead up to an ask for a major gift.

PUBLIC PHASE

By the time you’re ready to make a splash and go public with your Capital Campaign, the hardest work and the biggest goals will be behind you—and you’ll feel confident that your Campaign and its goals will resonate with your audience.

This is where your communications strategy and marketing materials really come into play: emails, SMS messages, social media posts, videos, earned media, and advertising are all tactics you should consider to get the word out as widely as possible and build a strategy to generate more interest and the ability for anyone to contribute to the Campaign.

Ready, set, go

Once you’ve built your team, excited your Board, conducted a feasibility study and addressed any findings, developed a campaign budget and a case for support, created a gift chart, assessed your donors’ giving potential and developed a prospect list and strategy, and put together an innovative communications plan, you’ve got all the components of a Capital Campaign strategic plan ready to go.

In our next article, we’ll dig a little deeper into what happens when the quiet phase begins and more about the strategies and tactics you should look to make up both phases of your campaign to get you to your goal on time and one step closer to realizing your organization’s vision for the future.