In Atrómitos’ final article of 2020, I wrote about the need for 2021 to be the year we address the myriad wicked problems confronting our nation. In keeping with that theme and also given that the North Carolina General Assembly, along with many other state legislatures, has recently convened for its new session, I want to talk about Medicaid expansion.

As of January 2021, almost a decade after states gained the ability to expand Medicaid, twelve states still have not expanded Medicaid: Wyoming, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Kansas, Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina. While a vast majority of states–38 states plus the District of Columbia–have expanded Medicaid for their citizens, many are left with the question: What is stopping the remaining 12 states from taking advantage of considerable federal funding in order to extend health insurance to low-income adults in their states?

FIRST, SOME HISTORY.

Created in 1965, Medicaid is an entitlement program that provides health insurance to certain low-income individuals. Medicaid is jointly administered by the federal and state governments. The federal government sets minimum standards, but delegates broad flexibility to the states as it relates to eligibility, covered services, administration, and payment. The program is funded with federal and state dollars based on a formula called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). In North Carolina, as an example, the split in funding is generally two-thirds federal dollars and one-third state dollars.

Under the traditional Medicaid program, not all individuals who are low-income qualify for the program. It is generally only available to children, individuals with disabilities, pregnant women, and some parents. The inclusion of these specific populations was intentional, as they were largely outside of the workforce and so did not have access to insurance through employment. By including these initial non-controversial populations, the framers of the Medicaid program intended it to be the first step in providing coverage to all low-income individuals.

While the framers intended for Medicaid (and Medicare) to be an incremental approach to providing universal coverage, political inertia resulted in no meaningful action at the federal level until 1997 when the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was created. Then finally in 2010, almost 50 years after Medicaid’s initial creation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted, though many of its provisions did not take effect until 2014. The ACA marshaled in the greatest expansion of health insurance coverage since 1965.

You might be wondering, “What happened that we finally overcame the political inertia?” The answer is that the problem of the uninsured and underinsured had become so bad that it just could not be ignored any longer.

By 2009, over 15% of the population (more than 46 million people) was uninsured and 11% of the population underinsured. This lack of insurance not only resulted in no or limited access to routine care but was also a leading driver of economic instability for individuals and families, with high rates of both medical debt and bankruptcy resulting from medical debt.

Employer-sponsored insurance access declined year-over-year for a decade leading up to the ACA, in part because of the Great Recession in 2008-2009. However, it should be noted that declines began before that because of affordability concerns. Between 2000 and 2010, health care spending grew from $1.4 trillion to $2.6 trillion with no corresponding improvement in health outcomes or quality of care.

So in 2010, with this catastrophe to contend with, the Obama Administration and Congress sought to reform the U.S. health care system.

Every reformer comes up against a foundational question when trying to tackle the issue of health care reform in the U.S. and that is: Do we build upon the existing system of private insurance or scrap private insurance as the bedrock of the U.S. system? Insurance carriers and their related activities represent about 3% of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP)–or almost $1 trillion. Taking on an industry of that size is no small feat.

And so, for all its controversy, the ACA is predicated not only on the principle of incrementalism, but also more traditionally conservative principles, such as the primacy of the market and free enterprise. Rather than being a full system overall, the ACA must be understood first and foremost as a reformation of the insurance industry with the limited objectives of addressing long-standing problems endemic to the system.

However, relying on private health insurance presents challenges that the ACA attempts to address including:

- “The Free Rider Problem”

- Ensuring healthy people participate (avoiding “death spirals”)

- Addressing variability in quality, affordability, and coverage

Now at this point, I’m going to guess you’re saying, “Okay, great. But what does all this have to do with Medicaid expansion?”

I’m getting there. Promise.

How these problems are addressed is often visualized as the three-legged stool in which standardization, the individual mandate, and premium subsidies are leveraged to make insurance more accessible and affordable for many. But no matter the extent of the insurance reforms, there is always going to be a segment of the population that cannot afford private insurance. To address this need, the ACA mandated expansion of Medicaid. (See, I told you I was getting there.)

The ACA mandated state expansion of Medicaid to all residents under 138% of the federal poverty line (FPL) and provided 100% federal funding for the expansion (gradually reducing to 90%). For states that expand after 2020, the federal government will pay 90% and the state will pay 10% for those in the expanded category.

Like everything with the ACA, the mandate was challenged in court, and in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Medicaid expansion was permissible but that states had to be permitted to choose to expand. So, the mandate became an option.

States then had the power to choose to implement Medicaid when the program was originally enacted in 1965. Then, as now, not all states rushed to do so. North Carolina was among the last states to implement Medicaid originally, not implementing until 1970.

WHO FALLS IN THE COVERAGE GAP?

The ACA has resulted in a reduction in the uninsured, dropping from 15% in 2009 to a low of 8.6 in 2016. Since 2016, there has been a steady increase in the uninsured rate, reaching 9.2% in 2019, still well below the uninsured rates prior to the ACA. One of the drivers of the uninsured rate is the states that have failed to expand Medicaid. As an example, as a result of not expanding Medicaid, North Carolina consistently has among the highest rate of uninsured nationally. Pre-pandemic, the uninsured rate in NC was about 15% and it increased to 16% for adults ages 18 to 64. When you look at rural counties, the rate of uninsured is as high as 29%.

This lack of coverage drives North Carolina’s poor health outcomes and life expectancy, with North Carolina consistently ranking in the lower half for outcomes.

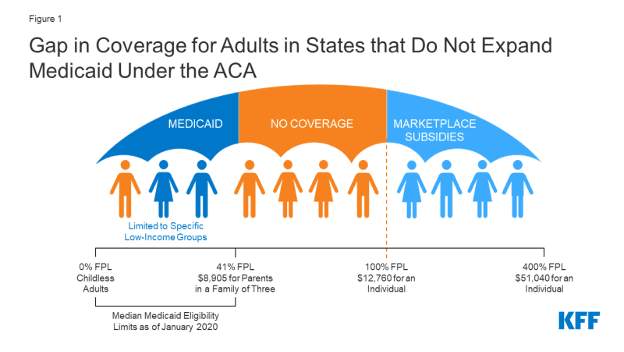

So what is the coverage gap? As I described above, for individuals with incomes over 138% of the FPL, the ACA provides access to subsidized private insurance coverage through premium and cost-sharing tax credits, significantly reducing the costs of private insurance. For those under 138% of FPL, they are able to access coverage through Medicaid.

Remember, when the ACA was created, Medicaid expansion was mandatory. So, this made sense. When the Supreme Court ruled that Medicaid expansion had to be an option, that left tens of millions of people without access because they cannot access Medicaid and have no reasonable access to other forms of coverage.

Nationally, in 2019 (pre-pandemic), more than 2 million adults fell into the coverage gap. North Carolina alone accounts for about 10% of those individuals. Ten of the 12 states that have not expanded are located in the Southeast, accounting for 97% of individuals nationally in the coverage gap.

The vast majority of people in the coverage gap are adults with children. In North Carolina, parents only qualify for Medicaid if their income is at or below 43% of FPL ($9,443.00 annually for a family of 3). More than 60% of the population in the coverage gap are between 18 and 44 years of age. Approximately 48% are white, non-Hispanic and about 52% are people of color. The vast majority are working, often in low-income jobs and industries that don’t offer employer-sponsored insurance.

OBJECTIONS TO MEDICAID EXPANSION

Those who oppose expanding Medicaid typically cite one or more of the following four reasons:

- It will cost too much.

- It will prevent people from working.

- It is legally uncertain.

- It will put more people in a broken system.

Let me address each of these directly.

1. It will cost too much

As described above, Medicaid expansion is 90% paid for by federal dollars. This federal match is not time-limited but will remain at 90%. For the traditional Medicaid program, the federal government pays less than this in all states. I’d argue, instead, that it costs too much not to expand.

An analysis from the NC Justice Center found that if North Carolina had expanded Medicaid in Fiscal Year 2019 (July 2018), the state would have saved $100 million in state dollars over a two-year period. This is, in part, because services that are currently covered only by state dollars would be covered by Medicaid, which would be paid at 90% by federal dollars. The study also estimated a $56 million reduction in uncompensated care to hospitals because individuals would have coverage through Medicaid.

There is no truth to claims that expanding Medicaid will result in huge increases in state budgets. In fact, studies of states that have expanded have shown reductions in state budgets and an increase in state revenue through additional taxes from new employment and increased business.

Further, if North Carolina had expanded Medicaid in 2019, the state would have received $12 billion in federal funding between 2020 and 2022. It makes little sense to leave this money on the table at any time, but especially in the midst of a public health crisis that has left millions unemployed and uninsured.

2. It will prevent people from working.

The vast majority of individuals that fall in the coverage gap are employed. In fact, they are employed in industries or roles that do not often provide employer-sponsored insurance, such as construction, farming, retail, janitorial, and home care. For those who are not working part-time, full-time, and/or in school, there are reasons such as being a caregiver or having an illness/disability that prevents work. See the article we wrote in December about Medicaid work requirements for additional information on this issue.

Also, this notion that providing individuals with insurance coverage would prevent them from working fails to recognize that they have other financial obligations that require work, including paying rent, buying food, and other essential needs.

3. The legality of the ACA, and therefore, Medicaid expansion, is too uncertain.

We, along with numerous legal scholars, think that the Supreme Court will uphold the ACA (hopefully once and for all). But, even if by some chance the Supreme Court doesn’t uphold the law, it is likely that the Biden Administration with an (albeit barely) Democrat-controlled Congress would resolve the legal defects. Either way, we don’t think that there will be legal barriers for states to move forward with Medicaid expansion.

4. Medicaid is a broken system and we shouldn’t put more people in a broken system.

There is no meaningful evidence that Medicaid is a broken system. Like all aspects of the U.S. health care system, it could use improvement. We know that there are lower levels of provider participation in Medicaid than in Medicare, but despite this, enrollees have access to regular sources of care, receive important preventative services, and have access to specialists.

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates the improved health and economic outcomes for individuals and communities when people are covered by Medicaid, rather than being uninsured. In fact, Medicaid enrollee satisfaction surveys demonstrate that those enrolled in the program are satisfied with their coverage and access to care.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MEDICAID

Since 1965, Medicaid has grown in importance to individuals, health care providers, and our communities. The importance of Medicaid today cannot be overstated. Medicaid provides insurance coverage to more than 70 million people in the country. In North Carolina alone, over 2 million people are enrolled in Medicaid, about 75% of which are children under the age of 18. Medicaid accounts for 20% of health care expenditures nationally, is the primary payer for long-term care (accounting for more than 50% of LTC expenditures), and is the largest payer of behavioral health care (26% of spending). In North Carolina, Medicaid covers more than half of the births in the state.

Medicaid has resulted in significant improvements in health including, for example, a considerable reduction in infant mortality (26 per 1,000 live births in 1960 v. 5.7 per 1,000 live births in 2018). Medicaid also enables the private insurance market and Medicare to operate more efficiently and affordably. For example, by providing coverage to individuals with disabilities, Medicaid alleviates the cost that private insurers would incur if individuals with disabilities had to otherwise seek coverage from private insurers.

Medicaid is also a vital component of our social safety net, keeping millions of Americans from incurring large medical debt and further increasing rates of poverty. Finally, Medicaid is critical to addressing the opioid crisis in the country, providing treatment to 40% of adults with opioid misuse disorder.

And we can’t gloss over the fact that this all comes at a significantly reduced price to the states because the majority of the cost is covered by the federal government. So, while the NC Medicaid program costs $15 billion, it only costs North Carolinians about $4 billion (one-third) and the remainder $11 billion is paid for by federal dollars. Absent the Medicaid program the state pays for all of it or people go without.

IMPACT OF MEDICAID EXPANSION

There have been more than 200 studies that have demonstrated wide-ranging positive impact—from improvements in healthcare to financial stability to decreases in unemployment— in the states that have expanded Medicaid. These outcomes include:

- Increase in access to care and more appropriate use of care (ex. primary care access v. use of Emergency Departments)

- Increase financial security, including reductions in medical debt and related bankruptcies

- Reduction in people living in poverty

- Stabilization of the health care system, particularly those in rural areas and safety net providers

- Stabilization of premiums in the private market, particularly ACA marketplace plans

- Increase economic growth, including increases in jobs created and retained

- State budget savings

In states that have not expanded Medicaid, not only is the uninsured rate higher, but these states also have greater problems with affordability of private insurance and higher rates of hospital closures.

The consequences of not expanding Medicaid are even starker in rural areas. This is of particular importance in North Carolina, the second-largest rural state in the nation (behind Texas), with 80 of its 100 counties considered rural. Between 2014 and 2019, North Carolina lost six rural hospitals. Nationally, 76 rural hospitals closed, with 83% of closures occurring in states that had not expanded Medicaid. COVID is likely to further exasperate rural hospitals driving further closures. Closure of rural hospitals is particularly troublesome, as this is often the only source of care for people in rural communities – regardless of insurance coverage.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Above all, expanding Medicaid in the remaining states will take compromise. As we described in our final article for 2020, addressing wicked problems will take many things. Compromise, especially on this issue, is front and center.

We have to put aside the partisan political theater and truly look at the problem and the available solutions and work to achieve the best outcome for as many people as possible. Compromise and collaboration are what ultimately led to Medicaid expansion in Indiana, for example.

This means that legislators will have to work across the aisle. Governors will need to work with legislators. Hospitals and health plans will need to agree to assessments. Providers will need to accept that expanding Medicaid is the best way to get people insured–and that being insured is far better than not.

Citizens will need to understand the importance of Medicaid to so many in their community and that expanding Medicaid has a meaningful impact on those who are not in Medicaid, through improved sustainability of health care systems, more stable and affordable private insurance, increased job opportunities, and a healthier community.

For those who support Medicaid expansion, this is your call to action. For the last few years, many have written off legislators who oppose Medicaid expansion as simply “ungettable” votes. I even admit to holding such an opinion. In the spirit of making 2021 the year we deal with these wicked problems, I commit to using the art of persuasion and engaging with opponents of Medicaid expansion to collaborate and compromise to find a path forward.

In fact, Medicaid expansion is actually supported by traditional conservative priorities including:

- Market Efficiency – Medicaid allows for the stabilization of the health care market to allow for improved competition among stakeholders.

- Fiscal Conservatism – Medicaid expansion is primarily funded through federal dollars. This allows states to leverage state resources elsewhere, maximizing impact.

- Entrepreneurialism and Employment – Access to Medicaid is associated with self-reported improvement in finding and keeping employment. The expansion has also created new jobs (within the health care industry, but in other industries as well).

At Atrómitos, we are committed to collaboration, compromise, and smart solutions. We are eager to work with stakeholders on this particularly wicked problem to find a solution.