In healthcare, there are (almost always) going to be more questions than answers. Every so often there is an issue where the solution is transparent and compelling. However, telehealth is an example that falls into the more questions than answers category.

For years when asked what providers need in order to adopt telehealth the answer back to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been a simple and resounding “SHOW ME THE MONEY.” Unfortunately, while studies have demonstrated the cost savings associated with telehealth adoption, it has taken a global pandemic for CMS to finally get on board with paying for telehealth.

In this article, we begin with an overview of the regulatory and policy limitations that were in place prior to the implementation of the Public Health Emergency (PHE) Act. We will then outline the temporary changes that have been made at the federal level to increase the adoption of telehealth. Finally, we will conclude by highlighting the regulatory and policy changes that providers are urging Congress to keep in place to facilitate continuous innovation and growth of telehealth services.

Pre-COVID Telehealth Reimbursement Policy

MEDICARE

Federal Medicare regulation has long been a guidepost for telehealth reimbursement in the U.S. healthcare system. The narrowly construed definitions import limitations on where telehealth services may take place, both geographically and by facility, as well as what services are covered. Specifically, in non-emergency times (under current federal law), Medicare reimbursement for telehealth services is only available when the service originates from an allowed setting which is limited to a clinic, hospital, or certain other types of medical facility and that originating clinic/hospital/facility is located within an officially designated rural health professional shortage area.

Only in very limited circumstances does an allowed setting include a patient’s home. Therefore, prior to recent emergency changes due to the pandemic, Medicare beneficiaries had to leave their home and go to a care site to access telehealth services.

While that may seem hard to believe in the current environment where we have leveraged telehealth to enable us to remain sheltered in place or under quarantine, prior to COVID-19 telehealth was primarily viewed as a means of expanding the provider network. So, when a specialty provider was needed for consultation, the patient would go to the primary care office (originating site) for the visit and the specialty provider would join remotely from their office (distant site).

This context shines a light on the paltry utilization of Medicare telehealth services prior to COVID-19. Only 14,000 beneficiaries received a Medicare telehealth service in a week prior to the public health emergency (PHE) as compared to over 10.1 million beneficiaries that have received a Medicare telehealth service during the PHE from mid-March through early July of this year.

MEDICAID

Federal Medicaid statute does not recognize telehealth as a distinct service. Rather, telehealth is considered a “modality of service provision.” Because there is no federal definition or criteria, states have a great deal of flexibility when designing their telehealth coverage policies. States have the option to determine whether (or not) to utilize telehealth; what types of services to cover; wherein the state it can be utilized; how it is implemented; what types of qualified practitioners or providers may deliver services via telehealth; and reimbursement rates. If the State Medicaid program has managed care, telehealth reimbursement can also vary from plan-to-plan.

State Medicaid and other payers generally model their telehealth policy approaches off what Medicare does. As such, changes to the Medicare program have a ripple effect throughout the rest of the healthcare coverage landscape.

COVID-19 Temporary Telehealth Reimbursement Policy

MEDICARE

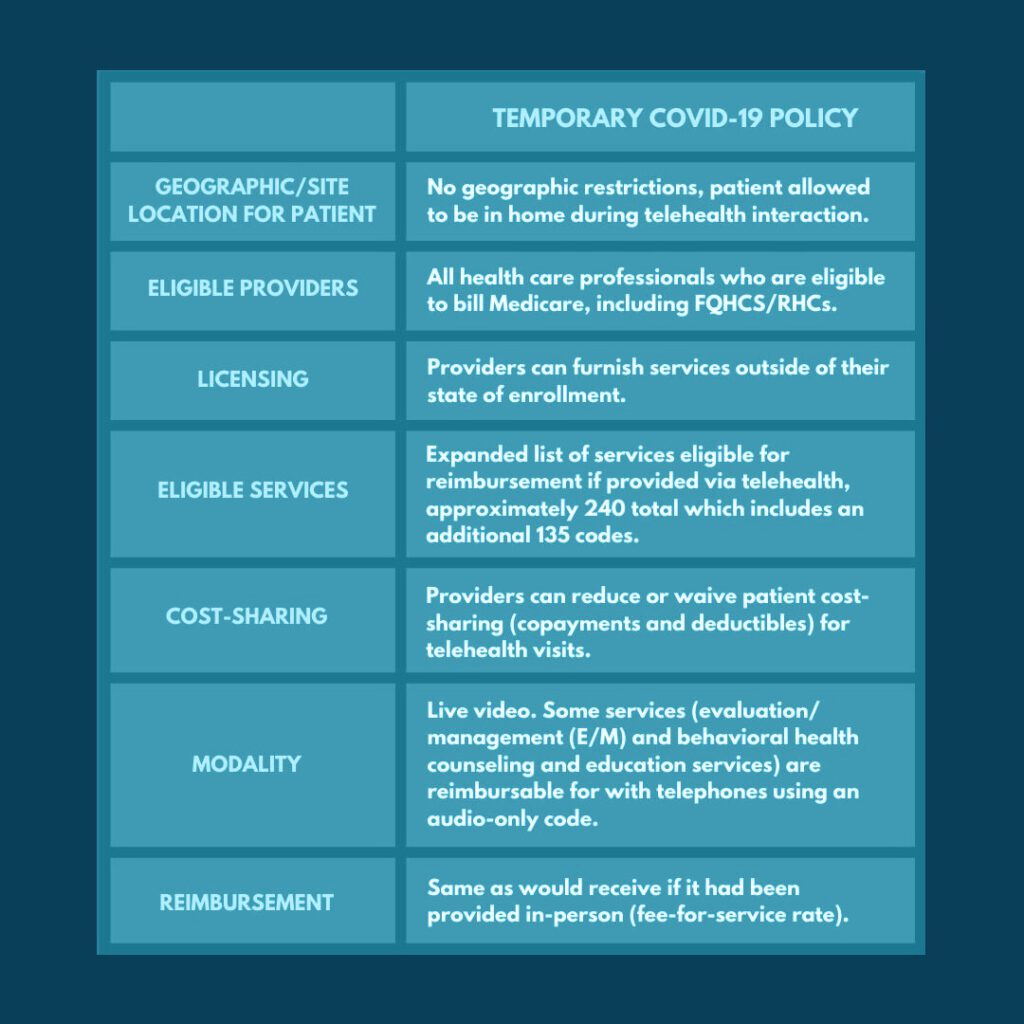

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, by way of Congressionally approved emergency powers, CMS enacted policy changes to expand payment for telehealth services and implement other flexibilities so that Medicare beneficiaries across the country can receive care in their home and avoid exposure to the virus. Some of the important changes to Medicare telehealth coverage and reimbursement during this period are summarized in the table below.

MEDICAID

As a result of the flexibility federal Medicaid regulation permits, telehealth coverage differs significantly from state to state. CMS created a toolkit to assist states in leveraging telehealth expansions in response to COVID-19. The guidance reinforced that state Medicaid programs have broad authority to utilize telehealth including using telehealth or telephonic consultations in place of typical face-to-face requirements when certain conditions are met.

Most states have expanded Medicaid coverage for telehealth during the COVID-19 PHE. For instance, many states are now allowing:

- Telehealth services via telephone, electronic and virtual means;

- Home as the originating site for telehealth; and,

- Coverage and pay parity for telehealth services.

The Center for Connected Health Policy maintains an inventory of COVID-19 Related State Actions that details each state’s requirements for billing telehealth during the emergency period.

Enacting Permanent Change

In speaking of the lifting of telehealth restrictions for the Medicare program, Dr. Eric Pifer, Chief Medical Officer at MarinHealth, said it was “the most important thing the government did to give providers the tools and flexibility to respond to the crisis.” And now a collective of 70+ providers, payers, and technology vendors are urging Congress to make the changes permanent.

While there have been 31 federal policy changes to expand telehealth service provision under the PHE, these stakeholders are seeking to ensure that ALL Medicare patients can access Medicare-covered services furnished via telehealth technology. To achieve this goal, advocacy is focused on the following provisions:

- Removal of the “originating site” rule so providers can be paid for an appointment regardless of where the patient is.

- Providing for Medicare-covered telehealth services to be furnished by Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Rural Health Centers (RHCs).

- Eliminating geographic restrictions that limit telehealth to patients residing in designated rural health professional shortage areas

- Allowing for the use of telehealth technology to conduct the face-to-face visit required to recertify a Medicare patient’s eligibility for hospice care.

If Congress does not act before the end of the PHE, coverage, and payment of Medicare services will (with a few exceptions) once again be limited to rural areas only, narrowly defined to exclude many rural parts of the country. Moreover, providers would be prohibited from delivering services via telehealth to patients in their homes, and Medicare beneficiaries, some of our most vulnerable members of society will be forced to travel to health care sites to access care.

According to the American Medical Association, “Pulling these expanded digital health capabilities away from Medicare patients at the end of the PHE would be a grave mistake for patients, providers, and government.” It is for this reason that the AMA and countless other provider groups support Senator Lamar Alexander’s bill S. 4375—the “Telehealth Modernization Act of 2020.” Alexander’s bill focuses on making two key policy changes permanent: Elimination the originating site and the expansion of telehealth reimbursement to any eligible Medicare provider.

What would Atrómitos like to see

Let us be very clear: we support S. 4375. Though while we support it, there are other things we would like to see.

- Parity. As discussed in our third Telehealth piece, payment and service parity will remain a significant issue until a legislative solution is provided. The PHE has shown that, given the option, patients and providers are willing, and in ways prefer, to leverage tele-based platforms to extend the continuum of care without any noted decrease in quality of care provided.

- New patient relationships. During pre-COVID times, telehealth services were unallowable between a provider and a patient that was unknown to them; a face-to-face meeting was required to establish a new provider-patient relationship. This was (kind of) relaxed after the PHE declaration. Part of the intent of telehealth services is to meet patients where and when they are able to access care; we believe requiring patients to physically attend face-to-face visits acts against this intent. As such, we would like to see work done to (responsibly) codify this flexibility.