The year is 2014. The place is Birmingham, England. The City Councilor of Birmingham has received a document now known as the Trojan Horse Letter. This letter outlines a plot by Islamic extremists to systematically take control over local schools.

The problem with the Trojan Horse Letter? Two-fold:

- Such a plot was never uncovered; and

- (Perhaps more disturbingly) The author of the letter was never looked for identified.

These two things being true did not prevent Birmingham and the larger governmental infrastructure of England from implementing drastic changes in response to what many believed was a hoax. Such changes, many of which were implemented within weeks of the letter’s initial publication, involved enhanced counterterrorism measures, firing the entire governing body of a school that had increased student performance by over 50%, and blocking educators from teaching for the remainder of their careers.

(For the full story of the “plot,” you should listen to The Trojan Horse Affair podcast.)

Nine years after the Trojan Horse Letter debuted in the Birmingham media, one doctor-turned-journalism-student and one podcaster brought to light the inexplicable reality of this story. And as I listened to each episode of the podcast, I kept thinking to myself, “But wait…is this really inexplicable? I feel like it should be, because this is wild. But does that make it so?”

Then I remembered a line from the first episode of the podcast:

“Operation Trojan Horse has become a ‘social fact’ in Britain.”

The phrase social fact sounds, to me, akin to fake news and the stuff that makes conspiracy theories flourish. In other words: “social facts” cause problems.

That is not, however, what a social fact is; at least not innately. Social facts aren’t necessarily good nor bad. It is how we use them that is where the problems arise. And I think they complicate how we deliver healthcare.

The Social Fact

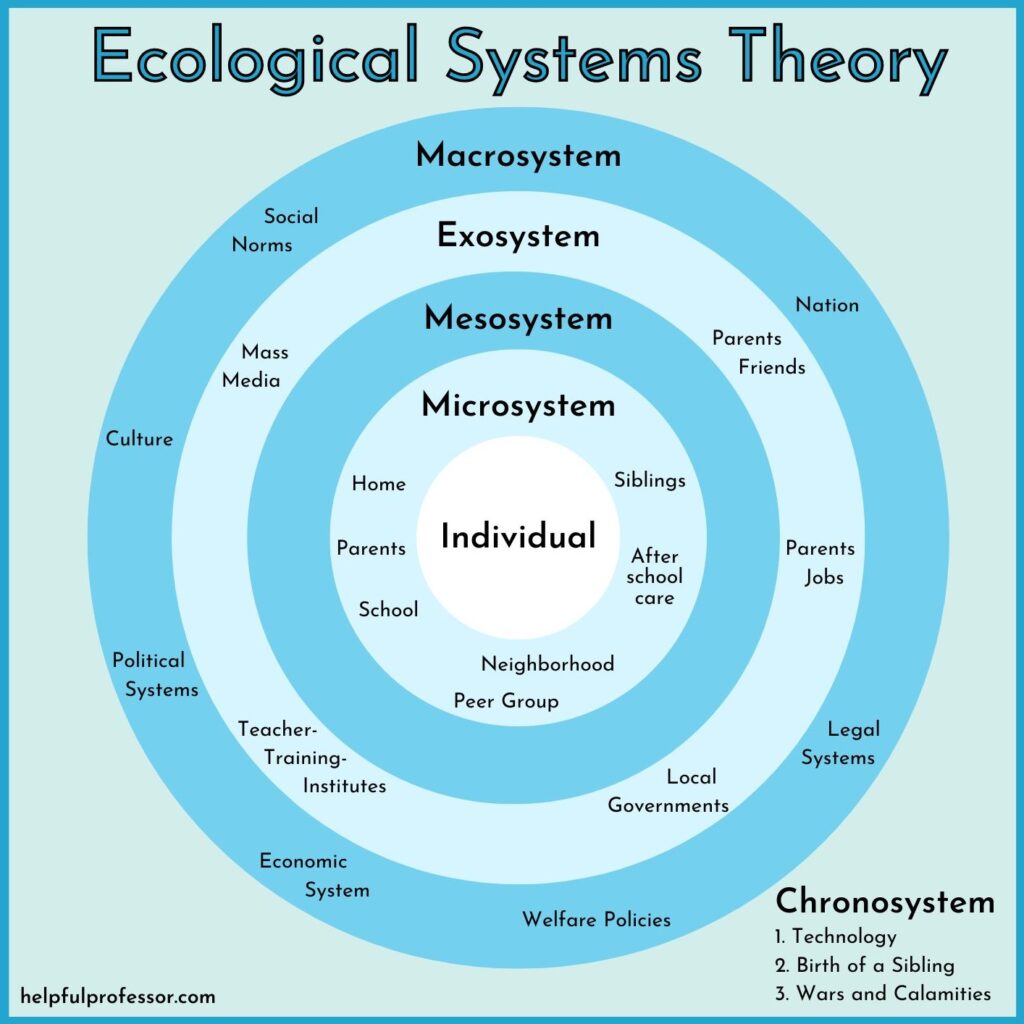

A quick 101 on social facts: Emile Durkheim originated the concept as part of his definition of what was sociology. At a high level, they “shape our attitudes, beliefs, and actions. They inform what we do every day, from who we befriend to how we work.” They are the Macrosystem in Ecological Systems Theory. They are also the focus of structural interventions, or attempts at changing our “structural context” to influence behavior. We are all impacted by them, and a lot of us in healthcare have spent some time trying to change them.

With this understanding, I had to reconsider whether I had anything new to say about social facts. After all, I have been actively working within, around, and alongside these constructs for the majority of my career. Then I realized it is not the mainstay social facts (think religion, political systems, cultural norms, etc.) that give me pause. Instead, it is what happens when our core social facts give rise to tenets or ideologies that, in and of themselves, move into the realm of a freestanding social fact that (potentially) alarms me.

Consider this: On behalf of the GOP, there is a national move to restrict (if not entirely eliminate) access to abortion services. From a healthcare perspective, this is wildly dangerous: reduced access to abortion services correlates negatively with health outcomes and economic stability. This also causes problems for the future of the GOP, as it is estimated that the majority of Americans favor some access to abortion services (including 35% of GOP-leaning voters [plus 29% who are “Unsure”]). For a political party that was not hardline pro-choice until the 1980s, this misalignment between party behavior and public opinion makes for a long road ahead. (This is especially true since reproductive rights are widely credited for the GOP’s underperformance in the 2022 mid-term elections.)

Also consider this: Since the murder of George Floyd, and the many subsequent deaths of members of communities of color at the hands of police officers, there have been multiple calls for defunding police departments across the country. Public polling on defunding police departments has shown a fall in those in favor of doing so. Despite this trend, left flank Democrats are embracing this movement (and albeit with some elected officials running and being elected on this and similar platforms [such as in my home base city of Chicago]). The challenge is that “defunding the police” is also inclusive of “reallocating funds” to community-based services that many believe can help reduce crime and the need for police intervention. From a healthcare perspective, the growth of this movement towards a social fact (along with its general misunderstanding and misconstruance) may deter voters from electing representation that they may otherwise agree with on things like access to mental health services and increases in the social safety net.

Social Facts Are Not Set In Stone

Perhaps the aforementioned walkthrough of social facts felt murky to you. (Don’t worry – it felt murky to me too.) The point I am trying to drive home is that many of us look to social facts to help guide our behavior. We turn to religion to help us understand morality. We trust our political leaders to guide us on what is best for the nation. We use the behaviors of those in our identified communities to keep how we act aligned with our support systems.

That is all fine and good. But what happens when the institutions we use to inform our behaviors start putting forth ideologies that begin to move away from our guiding lights? What work do we do (if any at all) to reconcile two competing social facts? And are we even aware which social fact we are leaning on for any given decision?

We tend to make a lot of noise about new and emergent things; after all, they are exciting and surprising. But those qualities do not necessarily make something, like a social fact, a good basis for behavior. As Frank Lucas (played by Denzel Washington) said, “The loudest one in the room is the weakest one in the room.” Obviously, this is not a universal truth – not every new thing is weaker or worse than its predecessor. But our current times of constant connectivity, never ending news cycles, bombarding social media, and the rapid ascent of the use of AI warrants a pause to seriously consider what we are consuming and how we are using it. After all, just because it’s a social fact doesn’t make it true.