Months ago when we first started our series on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the intention was to acknowledge an important anniversary (the failure of the 2017 Republican Congress’ efforts to repeal the ACA). We then turned to the judicial attacks on the ACA and examined the (then) pending Supreme Court case Texas v. California. Fast forward six months and four articles later, we are wrapping up the year along with this series; put it down to another thing that hasn’t gone exactly according to plan in 2020.

In closing this series, the natural question (with the Texas v. California decision expected in Spring 2020) is “what next?” I will be honest, in a year that has given us “Tiger King” and toilet paper hoarding, I am, at least for the space of these next paragraphs, giving up trying to predict what comes next. Instead, I would like to focus on what we know (and what we have known for quite some time). That is this: access to reliable, affordable healthcare for all members of a society is integral to our collective security.

The experience of the last year has been an object lesson on this point. Healthcare is not just a question of an individual right or benefit, but also a question of an adequate health infrastructure. Truly affordable access to care is a key metric of the health, stability, and resilience of any nation.

Every other developed nation has accomplished greater collective security through a national health program, guaranteeing a minimum level of coverage and access for all its citizens. This is done through various models, whether a single payer (like Britain’s National Health Service) or compulsory, private insurance regulated and subsidized by the state (like Germany’s system).

Here in the United States, we have struggled with this. As a result of our fragmented (non) system for delivering care, the U.S. spends more on health care, with a lower return on investment when it comes to overall quality of care and cost efficiency.

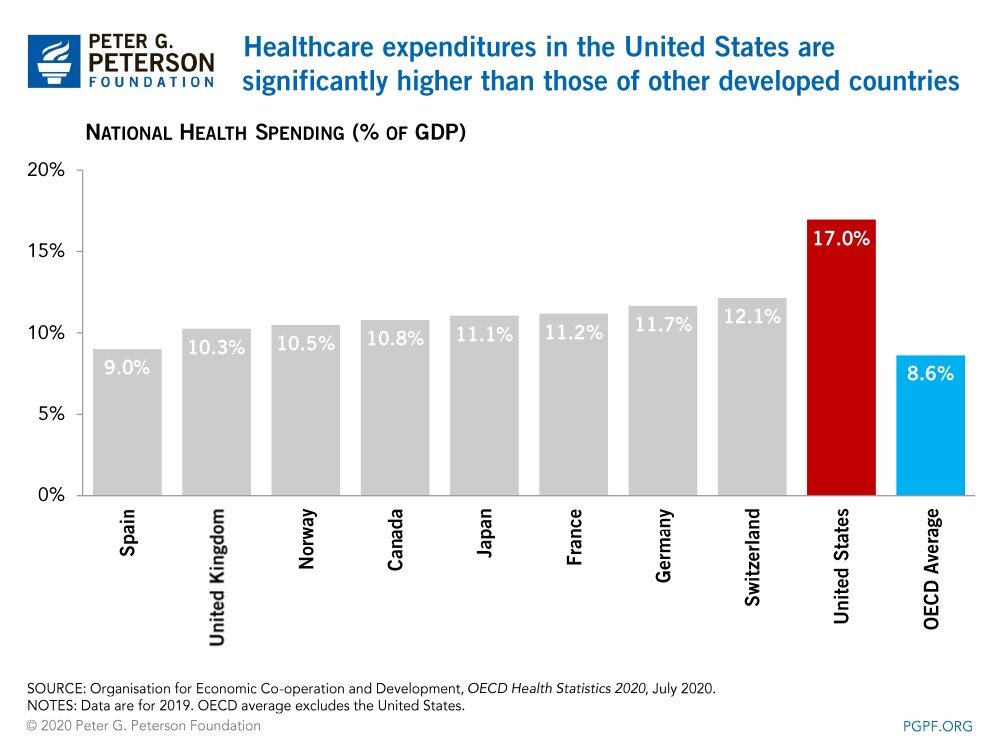

According to the 2020 Health Statistics compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S., as a percentage of national income, spends more than twice the average of other OECD countries. At the same time, the U.S. also has the lowest life expectancy among the other ten high-income countries, and the highest rate of preventable deaths.

Now, spending any amount of time looking through OECD health statistics and graphs is enough to make one think that “American exceptionalism” is not all it is cracked up to be. (Because we are policy nerds, you can find a good synopsis from the Commonwealth Fund here if you are looking for all of the depressing and frustrating deets).

There are many things that differentiate the United States from other developed countries, but perhaps the most important thing is the U.S.’s lack of universal health care or a true national health system. This leads to the next question: Why is this issue so hard for us here in the United States? Why, despite being arguably the wealthiest nation in the world, do we have some of the worst health outcomes among developed nations and the least security as it relates to health access and affordability?

In this article, we will examine these exact questions and offer two broad (and partial) answers to this conundrum. We will then turn to the history of health reform in the United States.

The Whys and Wherefores

There are a number of reasons for our failure, after more than 100 years, to find a solution to accessible, affordable health care. Among them, the American distrust of centralized government action and the correlating fragmentation of authority which is implicit in our federalist system and intentionally designed to obstruct the consolidation and exercise of centralized power. But, to this, I would add another component: money (money money). The U.S. may be the wealthiest country in the world per capita, but we may also be a victim of that good fortune.

LACK OF A TIPPING POINT

Fortunately, the U.S. has not faced the sort of prolonged, existential national crisis that has, historically, served as a tipping point for galvanizing the change necessary to overcome existing procedural and political roadblocks.

For example, the national health systems of most European countries developed out of the devastation of World War II. The shared experience of total war eliminated the “petty rivalries…and protective shabby fiefdoms” that had impeded previous progress (including, most notably, professional medical societies). There was also consensus for the need to create a “world fit for heroes,” and that, in that world, a state’s legitimacy rested on its capacity to serve the interests of its individual citizens, as opposed to the other way around. Indeed, plans for Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) and France’s universal insurance system (Régime général de la securité sociale) were being drawn up and circulated prior to the Normandy landings.

The U.S. has not faced anything on the scale of occupation by a foreign power (or the perennial threat of the same) as experienced by the Allied European states. Instead, after the war, the U.S. emerged as a hegemonic power, with a workforce and domestic economy built, in part, on the assumption of health insurance as a component of compensation. We have had the luxury of being able to hobble along, buffeted and hampered by that same surplus, and haven’t been forced to overcome our own so-called “rivalries and fiefdoms” in the face of a shared, sustained existential threat.

Baldly stated: If scholars point to a world war as the tipping point for this level of legislative change, that says something about the power of the status quo. This illustrates, at least in part, the real difficulty in instituting reform which has the potential to erode the prerogatives or profits of powerful stakeholders. And you can go ahead and treble that difficulty quotient where a legislative system (such as ours) is specifically designed with a bias towards inaction.

The power of the status quo and the preference for discrete, technical tweaks to an insufficient system as opposed to systemic change is further illustrated by the fact that access to health care is not a new issue. As we will discuss later in this article, this is an issue that every American President since Teddy Roosevelt has had to grapple with (not the Roosevelt you were expecting, eh?). And at every turn, each President (and this includes LBJ and Obama) has, with varying success, relied upon technical corrections to or expansions of the existing system as it relates to health.

MONEY (MONEY, MONEY)

This leads me to my second point: In the U.S., health care is big business with big (big) dollars attached. According to CMS data, U.S. health expenditures amount to over $3.6 trillion annually. That translates to a lot of stakeholders with a lot of stakes in the game. And the dealer isn’t in a position to call the game until the “house” can no longer support the run. To quote a political science professor of mine from graduate school, this dynamic can be reduced to a simple logic statement:

If BM, then FLH.

That is, where there is a big money (BM), those participating in the industry will “fight like hell” (FLH) to preserve their interests. And, as is often the case when it comes to legislation touching on #wickedproblems, there is a tendency not only to look for technical fixes but also to push those problems outside of the scrutiny of the spotlight. “Fixes” are themselves punted to bureaucratic administration, with numerous carve-outs, loopholes, ambiguities, and general operational complexities throughout the process in order to protect those various stakeholder interests, or at least leave wiggle room. The end result is compounded complexity – of an already complex system.

In fact, a common complaint when navigating the U.S. Health Care system is its complexity. Without devolving too far down a “chicken or the egg” line of thinking, it is important to recognize that this complexity is a feature of the system, not a bug.

A Timeline of U.S. Health Reform Efforts (with a few European Markers)

Keeping these two points in mind, namely (1) a bias towards inaction in the absence of an abrupt and sustained tipping point and (2) mo’ money mo’ problems – let’s take an (abbreviated) look at the evolution of health care reform in the U.S. over the past century.

- 1883: German Empire institutes first universal national health insurance scheme.

- 1911: The United Kingdom passes the National Insurance Act, which provided compulsory health insurance for lower-paid workers and instituted a capitation fee for physicians. Participation was restricted to workers and did not extend to dependents.

- 1912 Former President Teddy Roosevelt calls for universal health insurance as a tenet of the Progressive (Bull Moose) party platform in his Presidential Campaign. While his campaign lost, health care continued to be a priority nationally, as evidenced by….

- 1915: …The first model legislation for compulsory health insurance circulates in U.S. Congress. Published by the American Association for Labor Legislation, the model legislation was initially supported by the American Medical Association, who later withdrew its support in 1920.

- 1927: The Committee on the Costs of Medical Care, comprised of physicians, economists, and other stakeholders, is convened in response to the “alarming” rise in medical care, which was then estimated at 4% of the GDP. Chaired by Republican Ray Lyman (later to become the Secretary of the Interior under President Hoover), the committee drew over $1 million in funding, commensurate with the importance then attached to this issue. The Committee concludes that, in addition to expanded access to affordable care, there is a need for a federal role in standardization and management of care delivery.

- 1928: French Parliament passes legislation for compulsory social insurance (including health insurance) for low-wage workers in the industry.

- 1934-1939: President (Franklin Delano) Roosevelt creates the Committee on Economic Security in response to the Great Depression, with specific remit to evaluate old age and unemployment along with medical care and insurance. The Social Security Act is passed in 1935, while originally intended to encompass health insurance, health care was instead separated out and dealt with through the Technical Committee on Medical Care, which published its recommendations in 1938. Legislation based on these recommendations dies in Congressional Committee. The first Blue Shield plans and the federal Department of Health and Human Services are established.

- 1941 – 1943: The U.S. enters World War II in late 1941. In 1942, the federal War Labor Board institutes a freeze on all wages; this does not apply to fringe benefits such as health insurance. Employer-funded health insurance (and the generosity of benefits) becomes a widely practiced means of sidestepping these regulations.

- 1944: FDR identifies the right to adequate medical care as a component of his “Economic Bill of Rights” in his State of the Union Address. The Social Security Board subsequently calls for a compulsory national health insurance program in its annual report to Congress.

- 1945: France institutes National Health Insurance

- 1947: The UK institutes the National Health Services

- 1946-1948: National Health Insurance and The Fair Deal- Truman calls for National Health Program, picking up where FDR left off. Despite various congressional hearings and reports concluding the need for a national health system including universal coverage, the Hill-Burton Act (which funds the construction and financing of hospitals) represents the only substantive legislation to emerge out of committee during this time. In 1948 the American Medical Association launches a national campaign to counter-reform efforts, successfully stymying legislative efforts.

- 1960: The Kerr-Mills Act, a precursor to Medicaid, passes Congress and provides federal funds to states providing medical care to the poor and elderly.

- 1960 – 1965: “The Great Society” initiative headed by Presidents Kennedy and Johnson respectively leads to (1965) the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid.

- 1974: President Nixon outlines his proposal for universal health insurance in an address to Congress. Health care reform debate shifts from expanding coverage to that of cost containment.

- 1986: EMTALA requires hospitals participating in Medicare to screen and stabilize patients regardless of ability to pay.

- 1997: CHIP, providing health insurance for children and families just above Medicaid income eligibility, instituted by Congress.

- 2003: Medicare coverage expanded to include outpatient prescriptions

- 2010: Passage of the Affordable Care Act

Of course, the above timeline is just a snapshot of health reform activity and debate. Every President has wrestled with the issue of health reform, and if there is a pattern of a substantive step forward every quarter-century or so, it also only follows intense political campaigns and battles for public opinion. Before the putative “death panels” of the ACA debate, there was “Harry and Louise,” and always (always) the specter of “socialized medicine.” The history of health reform in the United States, therefore, reads like the “Groundhog Day” in political theater. We are having the same debates, facing the same (compounded) problems, and, generally, avoiding implementing the (already known) solutions. Our problem today remains the same as it was nearly a hundred years ago when the Committee on Medical Costs, responding to what was then viewed as an alarming growth in medical costs (then estimated to at 4% of GDP) concluded that: the basic problem of the American health care system is “not the system, but the lack of a system.” For all the (phenomenal) progress we have made in medical care and innovation since that time, that diagnosis is as true today as it was then.

Where do we go from here?

One would think that perhaps our tipping point is 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic running roughshod across the nation, resulting in unemployment rates exceeding those of the Great Depression and a corresponding loss of employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). With this loss of insurance, particularly for those living in states that have not expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate can be as high as 40%. So far though, even this catastrophe has not produced that tipping point.

In the Spring we will hear from the Supreme Court, hopefully for the last time, on the Constitutionality of the ACA. We predict that the Supreme Court will uphold the law. From there, we once again see Congress and the Administration making tweaks to the current “system” rather than pursuing fundamental changes that lead to a national health insurance program. That is, absent a coordinated, concerted push by the myriad healthcare stakeholders to once and for all find a “uniquely American” approach to expanding accessible, affordable coverage, not linked to employment or your state of residence, for the security of all.