Last week North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein announced his approval of the acquisition of publicly owned hospital New Hanover Regional Medical Center (NHRMC) by Winston-Salem based health system Novant Health Inc. Attorney General Stein’s announcement constitutes the last regulatory hurdle for the controversial $1.5 billion dollar acquisition. Novant Health assumed control of the Wilmington-based hospital effective this week.

This purchase will make Novant Health the dominant health care provider across southeastern North Carolina. This consolidation in a state with an (existing) exceptionally high concentration of health system market share, as well as the loss of an important publicly managed resource, has garnered both national attention as well as local controversy. As Attorney General Stein observed in his statement last week, the consolidation of community hospitals into a larger health system raises “real concerns about what this means for the future of health care in North Carolina.”

Some of this attention is a function of the nature of NHRMC as a publicly owned hospital and resource. As a recent Fortune article aptly points out, publicly owned hospitals are an “increasingly endangered species.” NHRMC was all the more unique as it was one of the largest and most financially secure county-owned facilities in the nation. It was one of those rare breeds: a publicly owned hospital that actually made money. In fact, in 2019, the year NHRMC announced it was seeking a purchaser in order to obtain access to greater capital investment for identified upgrades, the hospital reported $110 million in profits. The sale of NHRMC has left many to wonder if this self-sufficient hospital cannot stand, what hope is there for other public hospitals?

Well, the answer is: Not much.

THE ARGUMENT FOR CONSOLIDATION

This raises the question of whether this—the diminishment of independent and publicly-owned hospitals and the rise of health system “leviathans”—is a bad thing for the healthcare ecosystem. The past year has demonstrated the importance of a well-resourced and resilient healthcare infrastructure. Representatives of healthcare systems cite the operational efficiencies, economies of scale, and opportunities for improved clinical integration that can result from hospital consolidation.

Another argument in favor of the efficiency of consolidation is the expanded access to capital that follows consolidation. Indeed, access to the capital that is needed for updating hospital facilities and operations is frequently (as was the case for NHRMC) cited as a leading (if not primary) driver for hospitals seeking a purchaser. This is particularly the case for rural or publicly-owned facilities. Access to capital is critical, but not just for updating facilities or purchasing new medical equipment. The cost of new or expanded EHR systems and the clinical integration required for effective population health operations can be….substantial to the point of staggering.

However, it’s not quite that simple.

A SIMPLE ECONOMIC EQUATION

Unmanaged Competition + Market Forces = An Industry Arms Race

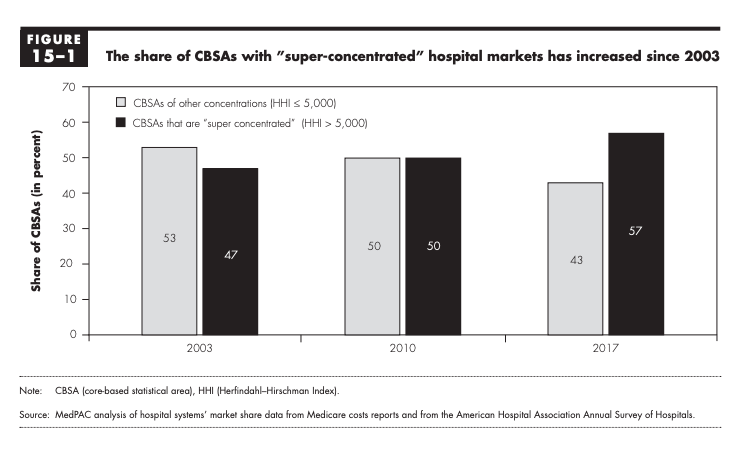

Greater access to capital and the potential for improved operational efficiency are two important drivers for (and benefits of) consolidation. However, the most important factor is more fundamental – and that is the drive for greater market share and the improved negotiating power that confers. Hospitals are not the only stakeholders that have been metastasizing over the past few decades. Health insurance companies have undergone a similar centralization process in the past few decades, as can be seen in the figure below.

Health payers are (naturally) incentivized to negotiate the lowest possible rates for health services across their network. Researchers at Harvard Medical School estimated that insurers with 15% or more market share contracted for approximately 21% less for services than carriers with lower market share.

Providers (specifically hospitals, but also independent providers) can counterbalance that impact through consolidation to command a greater market share and improved leverage in negotiations with payers. As summarized by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPac), in its March 2020 report to Congress on delivery systems and provider consolidation, it is generally accepted that provider consolidation leads to higher health care prices for private insurance. A recent study by the Nicholas C. Petris Center at the University of Berkeley attempted to quantify this cost by evaluating costs at hospitals recently acquired in 25 Metropolitan areas nationally. They identified an increase in the price of the average hospital stay, from 11% to 54% in the years following consolidation. Another analysis found that mergers of hospitals in one state resulted in a price increase of 7% to 9% at the acquiring hospitals. That rise in cost is significant, consistent, and concerning – but are we getting better value as a result of these consolidations?

The short answer is – probably not.

Despite the promise of improved care coordination and operational efficiency, evaluation of quality after acquisitions or mergers are mixed at best. Indeed, consolidation has also been associated with a decrease in quality and patient satisfaction, as demonstrated in a 2020 study in the New England Journal of Medicine which evaluated pricing at 246 acquired facilities.

Health economist Martin Gaynor summarized the function between consolidation, cost, and quality in his February 2018 testimony before the Energy and Commerce Congressional Subcommittee: “consolidation between close competitors leads to substantial price increases….without offsetting gains in improved quality or enhanced efficiency…[Indeed] evidence shows that patient quality of care suffers from lack of competition.

Moving from the general back to the specific (and specifically the sale of NHRMC and its impact on the cost and quality of care in southeastern North Carolina), North Carolina Treasurer Dale Folwell summarized his expectations succinctly (and bleakly):

“We should expect quality to go down, access to go down, [and] prices to go up.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Whether hospital consolidation is a defensive or aggressive move in the battle with insurance carriers, is a bit of a chicken and egg question – and not strictly relevant to the problem that we face today. That is this: The US health care system, as a non-centralized utility, is governed by market forces and market performance. That means that the health of the health system and infrastructure is only as strong as the markets that underlie it. These markets, for a variety of reasons, including the lack of consistent or vigorous government action, are not operating in an efficient manner. There is a deep (and growing) lack of competition in health care.

This is not a new issue. The trend towards consolidation, and its impact on competition and costs, has been a point of concern for over thirty years. In 1984, economist and systems engineer Alain Enthoven observed the danger of the arms race between insurance carriers and providers in the absence of “managed competition.” Other scholars at the time also attributed the (then) “skyrocketing rate” of increase in health expenditures to consolidation and called for more stringent government scrutiny.

But that was nearly forty years ago. Since that time, the issue has moved from a point of concern on the horizon to the predominant reality. Consider the following: In 2012, 25% of physicians were employed by a hospital or health system. In the space of eight years, that figure has raised to 44%. Or consider the fact that, across the majority of markets nationally, a single hospital system accounts for the majority of any inpatient admissions.

NEXT STEPS

There are things that we can do now to address and mitigate this issue. This includes, most significantly increased antitrust scrutiny and enforcement, but also a commitment to policies that support independent hospitals. This includes funding or additional grants for publicly owned facilities – particularly those serving rural or underserved communities. In its 2020 Report to Congress, MedPAC (which is specifically charged with controlling costs and ensuring value for Medicare dollars), made the unusual recommendation of raising certain rates, recognizing that current rates may be insufficient for some operations and further driving consolidation.

And here in North Carolina, need I add that Medicaid Expansion would go a long way in buttressing up the financial security of some of the most vulnerable facilities?

But we also need to recognize that these steps are long overdue – and the issue is one of great urgency. The MedPAC team essentially equated correcting course as a case of “unscramble[ing] the eggs” – what is done cannot be (easily) undone.

That is why Attorney General Stein’s statement expressing concern for the impact that this sale will have on the North Carolina healthcare market, and his assurance that he will advocate for a more “comprehensive system of review” with legislators, is cold comfort. As Attorney General Stein noted, the discretion granted to his office on these acquisitions is extremely limited, and while additional systemic state review is needed, (assuming the continued anemic approach exercised by the Federal Trade Commission), it is an example of bolting the barn door after fleeing horses. In a market where already 74% of the market share is attributed to health systems, it is simply too little – and too late.

We usually try to end our articles on a positive note, including recommended next steps. This week, we instead toast the end of one of the giants of public hospitals. It is a sort of Ragnarok – a twilight of the Gods and passing of a different time (and I raise an imaginary horn of mead to NHRMC) before we turn to another titanic challenge: cleaning the Augean stables of our increasingly non-competitive marketplace.