On August 4, 2021, The Commonwealth Fund released its Mirror, Mirror 2021 report, comparing health care in the United States to 10 other high-income countries. If you have spent any part of your career tracking the effectiveness and cost (and the relationship between those two variables) of health care in this country, the knowledge dropped in this report is most likely not a surprise to you. The long and short of it is that:

- the United States still pays more for its health care; and

- the care received in the United States for the cost is still lower in quality

(Although the extent to which the United States falls behind the countries of comparison may shock you: The United States scored so poorly on measures that we were treated as a statistical outlier and were dropped from analyses when calculating an average score for the remaining ten countries.)

Most of the report is a bit of the usual “doom and gloom” look at how the United States manages health care. Some good news – we did place second in the rankings for the Care Process measures, which include “measures of preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and engagement patient preferences.” But don’t get overly excited, as we placed last in the remaining four sections and overall.

SO WHAT DO WE DO ABOUT IT?

The Commonwealth Fund starts their discussion of the report’s findings by highlighting what the top-performing countries leverage to attain “better and more equitable health outcomes.” As you all probably guessed, universal coverage and the elimination of cost barriers top the list of differences between top- and low-performing (read: the United States) countries in these analyses. While we at Atrómitos are proponents of universal coverage, this paragraph is as much geography as the topic will get in today’s article. (Don’t worry – I am sure we will find other reasons to write about it again soon.)

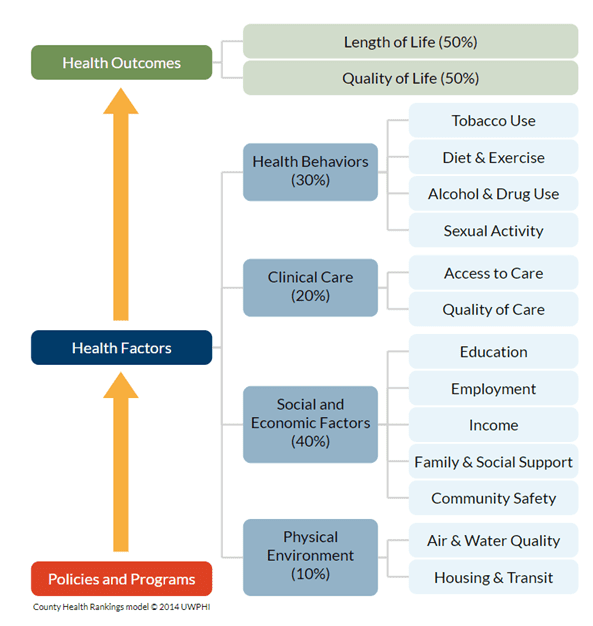

Instead, I want to spend time on item four of the report’s list of things that separate top- and low-performing countries: investment in social services. According to the authors of the report, the top-performers “invest in social services that increase equitable access to nutrition, education, child care, community safety, housing, transportation, and worker benefits that lead to a healthier population and fewer avoidable demands on health care.” Attention to these types of services, known more broadly as social determinants of health, has risen drastically in the United States in the recent past; and for good measure. Alone, social determinants of health (SDoH) account for an estimated 80% of the contributors to a person’s health outcomes (see Figure 1).

Given how much we understand these social factors influence health outcomes, it is puzzling why the United States has not stepped up its social service investment game.

My goal here today, however, is not to answer that “Why” question. Today I want to explore some ideas for your consideration on how to help propel the United States forward with diving into the social investment arena more whole-heartedly. Note that I am not selling these as the end-all-be-all solutions; instead, they are potentials that offer up an alternative to our current operating system that has resulted in the Mirror, Mirror 2021 findings.

SOCIAL INVESTMENT REQUIRES POLICY CHANGE, SO LET’S ELECT CATALYSTS.

The development and implementation of, and further investment in, social services and social reform movements frequently requires policies, regulations, and legislation (you can check out this history of social programs in the United States from the University of Chicago for more information). Many of the services we are aware of are those allowed for by federal acts. But social movements generally start at a grassroots level and definitely require connection to a local community to gain traction. This makes sense: much of what impacts an individual’s ability to remain healthy is specific to the geography within which they live. Those specifics can even include how a local geography implements, weakens or responds to a lack of social investment from the federal government (take, for example, the ongoing battle about evictions related to the COVID-19 public health emergency [PHE]).

With close ties to the community a primary requirement for acting on social needs, it becomes crucial that those elected to power are aware of and invested in addressing challenges, barriers, and inequities. Since 2003, Gallup polls have found that an increasing number of respondents (62% as of early 2021) believe that Democrats and Republicans are doing “such a poor job” representing the American people that a third major party is needed. However, the United States currently operates under and largely favors a two-party system of government, in no small part because most elections across the country produce a single winner.

If polls are finding the majority of Americans are looking for an alternative to the Democratic and Republican parties, maybe it’s time to rethink how we elect individuals into office. Enter, for example, Ranked-choice voting (RCV). In simple terms, ranked-choice voting is “an electoral system in which voters rank candidates by preference on their ballots” (thank you, Ballotpedia, for this definition). As of April 2021, nine states have implemented RCV at either a state or jurisdiction level, and seven other states have adopted but not yet implemented RCV (again, either at the state or jurisdiction level) (and, again, thank you, Ballotpedia, for this stat).

As with any election process, there are pros and cons to ranked-choice voting. But the reason for its inclusion here is because of one of the pro arguments. As described by Greg Orman, “Ranked-choice voting effectively allows voters to vote their actual preferences instead of having to vote strategically…It would empower independent and third-party candidates by eliminating the ‘wasted vote’ argument…Importantly, it would also allow voters to send a very direct message to elected officials about their policy preferences.”

SOCIAL INVESTMENT REQUIRES MONEY, SO LET’S CHANGE HOW WE SPEND IT.

You can’t discuss providing services without asking the questions of who will pay for them and how. (Let’s be honest: there are probably many other questions that need asking, but those are for another article).

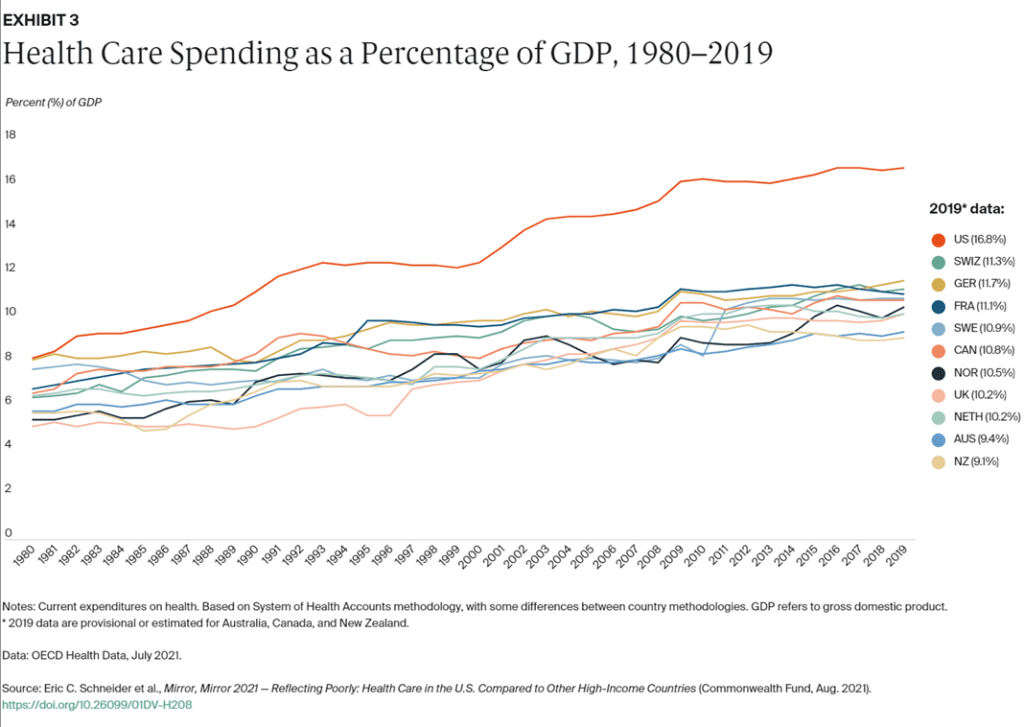

We spend a lot of money on health care (see Figure 2), and we are projected to keep increasing that spending as time goes on.

One area of health care financing that has attracted the ire of many, especially since the declaration of the COVID-19 PHE, has been the income of health insurance providers in the United States. Frankly, for good reason: health insurance companies are increasing their net income when many of us face confounding factors of financial instability. There are varying levels of satisfaction and effectiveness between commercial and public insurance. For example, commercial insurance beneficiaries reported lower satisfaction with, higher costs of, and poorer access to care than those covered under public insurance. However, the argument can still be made that there is room to grow in how we spend our health care dollars, specifically those given to entities responsible for ensuring we can access services necessary to achieve and maintain health.

What does this have to do with investment in social services? Simple: cover those services by health insurance. (Yes, that “simple” may have been flippant as doing so is a complex process). For most of our country’s history, we have operated under a medical model of health: diagnosis and treat the body and good luck with anything outside of the body that may impact health. But we know better now (and some of us have known better for quite some time): if the environment(s) around you do not support engagement in preventive and health-seeking behaviors, how can one be expected to remain healthy?

According to HealthCare.gov, health insurance is “a contract that requires your health insurer to pay some or all of your health care costs in exchange for a premium.” We know that social and environmental factors significantly impact our ability to achieve and maintain health. (You can refer back to the first part of this article if you need a refresher on this.) In that line of thinking, how have we not yet universally agreed that solutions to address social and environmental challenges are a subset of “health care costs”?

Some have started agreeing to this. North Carolina, for example, recently transitioned its Medicaid program to a Managed Care model. They developed and are actively working to implement what they have called Healthy Opportunities Pilots. These pilots are testing the impact of using Medicaid funding to address the social and environmental needs of Medicaid beneficiaries on improving clinical outcomes and reducing overall expenditures. Prepaid Health Plans in the state (known as Managed Care Organizations in most other states) are responsible for covering the costs of these services much like they are medical and behavioral health services. Pilot programs across the state are currently in development, with service provision scheduled to go live in 2022.

And yes, there are other models in the country of insurance companies stepping up and rethinking how they can better help patients achieve and maintain health outside of a provider’s office. However, a 2020 review of health insurance efforts around SDoH by the Center on Health Insurance Reforms found that “insurers use their charitable grant programs to combat SDOH problems, but they are not, in general, changing benefit designs, reimbursement policies, or other business practices.”

Can insurance companies make this change on their own?

No, doing so will require policy changes. And for that, I refer you back to the previous section of this article.

DID WE SOLVE ALL THE PROBLEMS?

No, no, we did not. But, as stated earlier, this article was not intended to provide the silver bullet solution. However, I hope that thinking about the concepts of ranked-choice voting and insurance-covered social services in the context of our poor performance in the Mirror, Mirror 2021 analyses has sparked some new thoughts or conversations for you. Yes, we have a lot of work to do to use our money more effectively to better care for those living in this country. If you have other ideas, I’d love to hear them.