This week, Tina Simpson is joined by freshman, an information security professional with 25 years’ leadership in cybersecurity, with a particular focus on medtech. In this article, Tina and freshman evaluate a critical cybersecurity capacity and infrastructure gap across health providers in the United States and call for stakeholders to re-evaluate their assessment of the costs of continuing to defer action.

October is CyberSecurity Awareness month. To mark the occasion, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (“CISA”) released a long-anticipated evaluation of the nation’s health provider cybersecurity infrastructure and operations related to the critical function of Providing Medical Care.

The results are not good.

But before we get to that, let us set the stage with an analogy we can all relate to:

You know that dream, where you suddenly realize that you are due to take a final exam in a course you didn’t know you were enrolled in? And (of course) the whole grade comes down to your performance because you didn’t show up to any classes, so in the remaining 20 minutes, you are frantically trying to make up for twelve weeks of blissful ignorance and digest the entirety of Differential Calculus for Dummies.

Well, that is this scenario – with the distinction that there are real-world consequences for our lack of awareness and preparation.

Now that we have your attention let’s talk about CISA’s report, which is snazzily titled: Provide Medical Care is in Critical Condition: Analysis and Stakeholder Decision Support to Minimize Further Harm. Because, while CISA’s findings and conclusions are much more diplomatically (and researcher-y) stated, it boils down to the same thing.

The main conclusions are these:

- Cyberattacks on health care providers present a critical risk to our collective ability to provide medical care.

- Health care providers have experienced an exponential increase in cyberattacks throughout the pandemic. This risk exposure will continue.

- The pandemic (and the wave of ransomware attacks on hospitals) has provided a unique and important opportunity to evaluate the impact a failure in cybersecurity defenses has on the healthcare system as a whole and the patients it serves. This includes a chance to extract the cost (measured in patient mortality) associated with cybersecurity failures from other confounding variables.

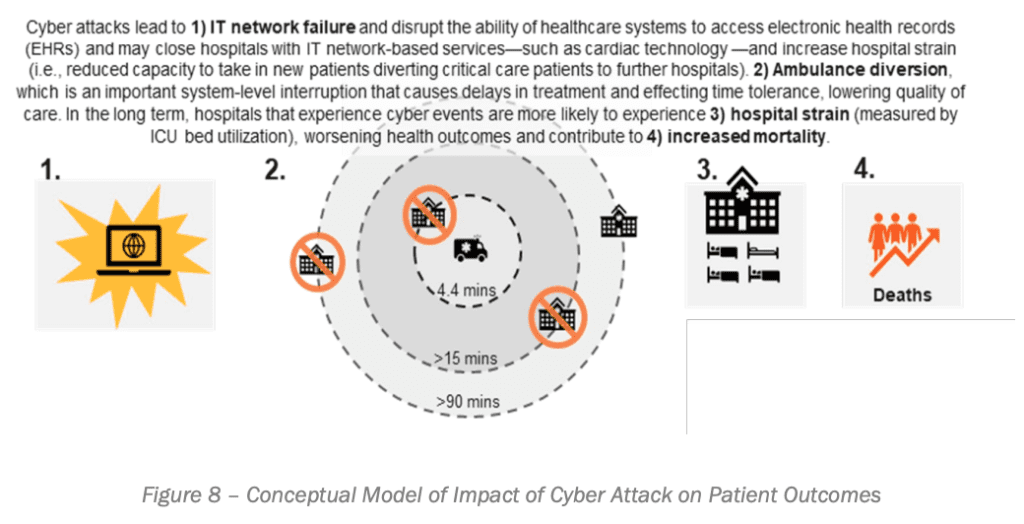

- More specifically (let’s talk methodologies here), CISA conducted a regression analysis of excess deaths experienced by hospitals experiencing a cyberattack. CISA defined “excess deaths” as the difference between expected and observed number of deaths in specific periods according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) while controlling for variables such as geography, size of facilities, and resources available. The analysis resulted in a model demonstrating the immediate and long-term cascading effects a ransomware attack has on hospital operations and patient outcomes.

- The report does not identify or disclose the excess mortality or poorer outcome rates associated with experiencing a ransomware attack. While this is a significant limitation, we must acknowledge the political, reputational, and legal pressures that inhibit such a disclosure. As an example, consider the pending lawsuit against an Alabama health system following the death of an infant who, allegedly, as a result of the diminished operational capacity of the facility, did not conduct routine tests that would have alerted the delivery care team that the umbilical cord was wrapped around the baby’s neck, leading to brain damage and death nine months later. Despite this, readers paying attention can likely infer that, using this analysis, there has been a quantifiable loss of life.

- The bottom line (for those in the back) being that ransomware and other cyberattacks present a clear, present, and pervasive risk to the delivery of care – and that necessarily includes the health, safety, and mortality of patients.

THE NEXT QUESTION IS WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT THIS

We propose that in addressing this problem, the first step is adapting our perspective on the risk ransomware actually presents. Because if we really believe that lack of cybersecurity infrastructure translates to a proximate and foreseeable patient harm, the next steps are more intuitive and self-explanatory themselves.

This means recognizing that the harm presented by cyberattacks and disruptions is not restricted to the legal or risk exposure created by a breach of private information or even in the interruption of operations. In the interests of creating a safe space, Tina will be the first to raise her hand to confess that, as an attorney and privacy and compliance professional, this legal risk exposure and compliance operations first comes to her mind. But this perspective fails to account for the fact that every element of hospital operations is impacted when IT operations and medtech resources are disrupted.

If we understand the risk in that context, IT and cybersecurity become something that we cannot continue (whether we intend to or not) to silo off in the background within an organization. It becomes a mission-critical function and would be reflected as such when it comes to organizational models, staffing, and resource allocation (including federal and state resource allocation to support under-resourced facilities).

Having written that, we recognize that that is a provocative statement. Hospital budgets, particularly smaller and rural hospitals, are working with razor-thin to vanishing margins. There is only so much they can do under the existing financial models. (File this under another reason for Global Budgets for Rural Facilities). If we care about (among other things) bridging the health care access gap between rural and urban systems, that translates to providing targeted and practical support to these facilities to address this gap – while holding all facilities to a consistent standard of baseline security. Anything less leads to a two-tiered delivery system, where smaller, more rural facilities will remain “softer” targets for cyberattacks, disrupting the health systems the least able to accommodate the disruption and safely divert patients.

LET’S WALK THROUGH WHY THIS MATTERS SO MUCH

The greatest risk presented by ransomware and other cyberattacks within the healthcare context isn’t financial risk or loss of personal information or identity threat or operational disruption, or reputational damage. Instead, according to Kevin Fu, the first Director of CyberSecurity at the Federal Drug and Food Administration (“FDA”), it is unavailability. It is the unavailability of the EHR and medical records providers need to deliver care.

The delivery of all health services is dependent upon a health systems IT platform and network. Disruption to that operation – whether in the immediate aftermath or on a longer-term horizon – necessarily results in denied or delayed (critical and chronic) services, more severe outcomes, and fatality, as is demonstrated in the following model from CISA.

SO, WHERE ARE WE AT THEN?

Now, having established the centrality of IT operations to an organization’s ability to deliver on its core mission to deliver patient care, we should next consider whether we (generally and collectively) are making a proportionate investment in establishing, maintaining, and monitoring the security of those operations and communications.

One statistic from a recent evaluation of information and cybersecurity operations and hospitals across the United States sticks in our minds. And this concerns the lack of cybersecurity.

An evaluation conducted in 2017 by the Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force found that the majority of health delivery organizations lack a full-time, qualified security member. More specifically, 85% or more of hospitals do not have a single staff member with the authority, qualifications, or experience to manage system-based cybersecurity operations. This problem is particularly concentrated in rural areas and among smaller and medium-sized hospitals, as the Task Force concluded in its 2017 Report to Congress.

We’ll give you a moment to digest those numbers and their implications, but we also want to note that this data is from 2017. Setting aside the stressors created by the COVID-19 pandemic (including the deferral of elective procedures and that impact on budgets), market forces have not improved since 2017 to enable small to medium-sized rural hospitals to, in general, drastically expand their capacity. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the state of employed cybersecurity officials within hospitals has not improved since that time, particularly when so many resources in the last year and a half have necessarily gone to responding to the public health crisis and providing direct patient care.

THE BOTTOM LINE

There are immediate steps that can (and must) be taken to manage this threat. But first among them is recognizing that lack of a cybersecurity defense plan (and the internal capacity to implement, integrate, and iterate) represents an existential threat to an organization’s ability to meet its mission – and a direct and preventable risk to patient health and safety. This translates to prioritizing cybersecurity operations and capacity development at every level of an organization.

Adjusting our framework thus is a first step – and a revolutionary one. “There’s such a palpable, visceral reluctance to admit that we’ve lost lives because of cybersecurity.” As Josh Corman, a senior advisor to CISA, reflected in reference to the 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack on the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, an attack which (among other things) shuttered all stroke centers in the Greater London Area. “The official line is that no one died. It strains credulity.”

What is different today from 2017 is that we now have the first direct analysis demonstrating the human cost of deferred action.