Since 1995 the American Public Health Association (APHA) has sponsored National Public Health Week as a time to recognize the contributions of public health in our communities and to highlight issues important to improving the health and resilience of our nation. Following our experiences of the past year, it is hard to think of a time in the recent past when that recognition and celebration has been more apt.

The theme for this year’s National Public Health Week is “Building Bridges to Better Health.” The APHA (in a manner characteristic of and dear to an epidemiologist’s heart) has methodically categorized each day of the week to reflect specific topics around this theme. The week started out, appropriately enough, on the topic of “Rebuilding.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has been an object lesson in the importance of a strong, centrally coordinated, and adequately funded public health infrastructure. It has also demonstrated how far we, here in the United States, have deviated from that model, and the consequences and challenges that follow.

It is time to remedy that—this includes a course correction of decades of chronic underfunding of public health authorities and the neglect of federal public health infrastructure, including (but not limited to) data surveillance and operational integration. It is—to borrow a long-running canard, “Infrastructure Week.” But this time, for real.

This brings us back to the American Rescue Plan (ARP) and, by extension, President Biden’s expected corporate tax plan (also known as the American Jobs Plan or AJP) intended to fund infrastructure investments. President Biden revisited the ARP in his Monday Proclamation opening National Public Health Week noting that the experience of the past year and the loss of over half a million Americans, has forced us to “come to recognize just how essential our public health efforts and public health workers truly are.” Acknowledging that this is a recognition overdue and too often neglected. He continues:

“While defeating the coronavirus is our top public health priority, our Nation must also focus on improving our overall health and wellbeing. Greater health is good for us all, and it will bolster our national resilience in the face of new and existing threats. The United States must prioritize and continually invest in our public health system to aggressively address health disparities that have been exposed and worsened by COVID-19. We must also address the environmental and climate factors—air and water pollution, extreme weather, and climate-related disaster events—that threaten public health in communities nationwide.”

Just as our built infrastructures have suffered following decades of neglect and underinvestment, the same is true of our public health architecture. Capital investment and the stabilization of existing operations is desperately needed; but is also not enough. I know, it’s rather bold to say that appropriations of over $88 billion to sustain and reinforce public health initiatives nationally “isn’t enough”—but it simply isn’t, if we stop there. Going forward, we need to evaluate the way in which we fund, organize, and prioritize public health as an essential component of an effective, efficient, equitable, and responsive national health strategy.

ALLOW ME TO EXPLAIN.

For decades—going back to the Hill-Burton Act of 1946, but picking up steam in the 1970s—the United States has made a “strategic commitment” to (1) developing and bolstering the hospital infrastructure and (2) biomedical research as the means of ensuring health care access, quality, and innovation. This has had many benefits such as the fact that the United States has led the world in medical innovation. But there have also been consequences, including that the United States has consistently performed poorly on more distributive metrics such as quality of care, access to care, and cost-efficiency.

To paraphrase Mr. Dicken’s, health care in America is a case of “it was the best of times; it was the worst of times”—with one’s experience within the broad spectrum dependent primarily upon one’s zip code and insurance status. Our failures in this are directly attributable to the neglect of our public health strategy, infrastructure, and operations, as outlined in a 2012 Institute of Medicine report.

If we are going to correct this, we need to look at the root causes of our system defects. And that means not just a one-time or sporadic capital injection following a point of crisis, but instead restructuring the way our public health system is financed.

A Picture (or Graph) is Worth a Thousand Words

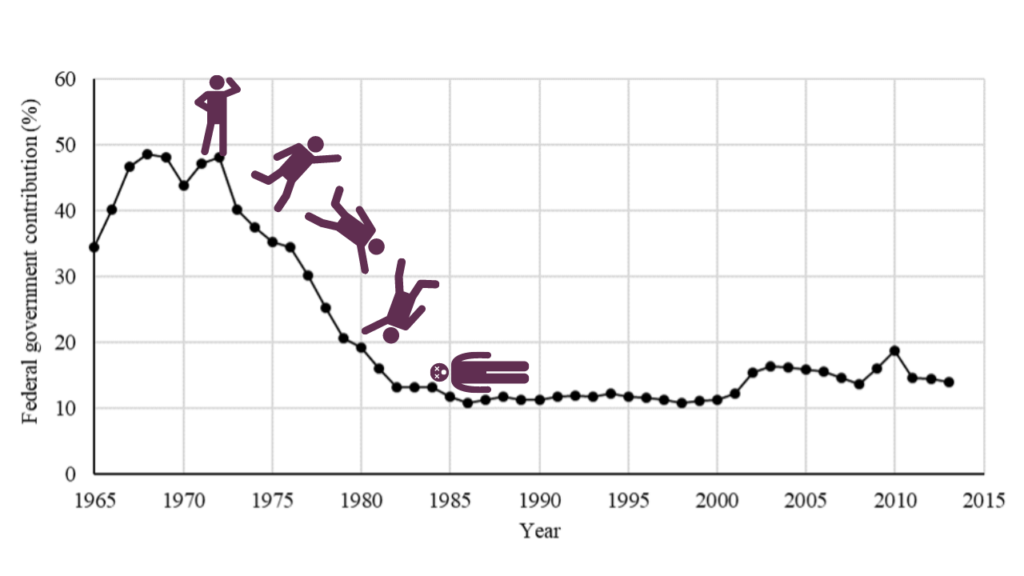

Figure 1. Federal Government Share of Total Public Health Expenditures

Note: The graph is very real, but we took a few liberties in our adaption.

Public health funding—like all parts of American social service financing—is fragmented and depends upon a variety of sources at the federal, state, and local levels. As demonstrated by the graph above, federal funding of public health took a precipitate decline in the mid-1970s and, excepting small “spikes” following focus on emergency preparedness following 9/11 and the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, has basically been flatlining.

Add to that that federal public health funding (as inadequate as it is) has often been diverted to direct health services financing. Consider the following: Although public health spending comprises a small portion of the federal health spending (approximately 2-3%), it has been subject to disproportionate cuts. These cuts, such as the 2012 raiding of the Prevention and Public Health Fund created by the Affordable Care Act to forestall Medicare physician fee cuts, are often made in order to further health services or to delay unpopular (and difficult) health system reforms.

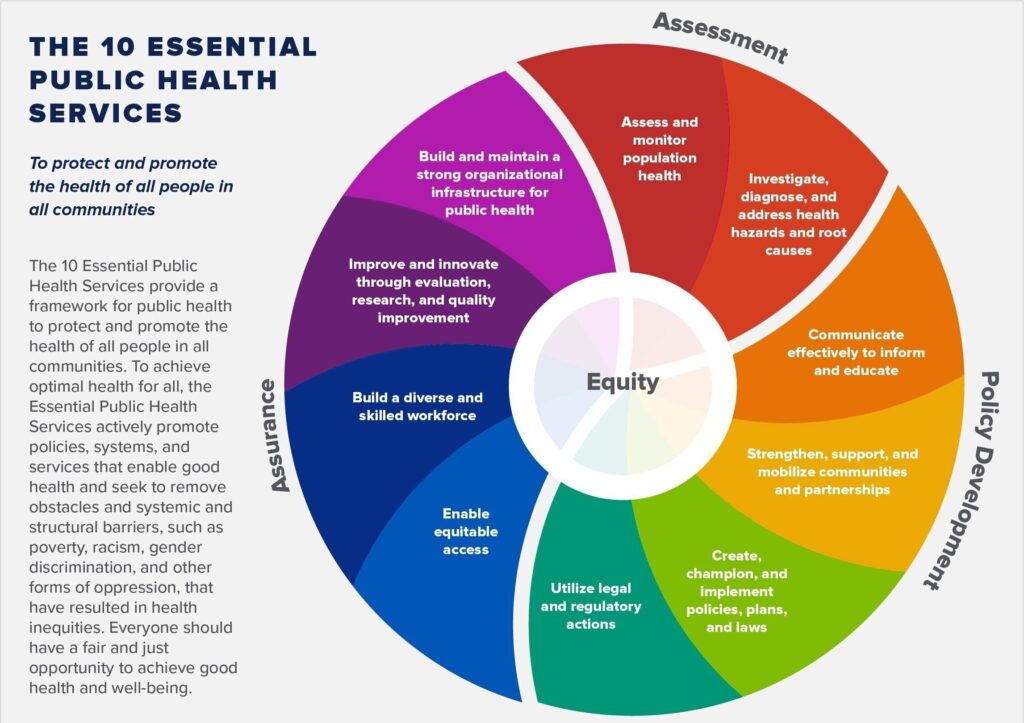

This is despite the fact that public health agencies are tasked with an increasing scope of influence and objectives—including the services detailed in the graphic to the right—and are of increased (central) importance in a value-based, population health-oriented system.

And that brings us back to the future of a more integrated (more resilient) rationale and equitable health model because public health and population health are at the core of this objective. To not utilize public health resources, expertise, and leadership is to throw away our best opportunity to deliver on the promise of “better health for all.”

When we talk about health reform—about getting better value for what we pay for and ensuring that resources are more fairly (and rationally) distributed across our communities—we are talking public health. Not just healthcare, health policy, or economics, or any of the other silo-ed disciplines. Public health is the congruence of these disciplines and it is time that public health practitioners take a bigger leadership role going forward. And we’re talking about leadership not just in moments of crisis (or on the question of “to mask or not to mask” Answer: mask), but as part of our strategy for a healthier, more resilient, more equitable, and (please) more cost-effective health environment.

This change in direction is more than a capital investment, however large. It is a reconfiguration of our priorities, objectives, and the means we use to get there.

For myself, I have been motivated by the opportunities inherent in the move to value-based care, in no small part because it relies on the inter-disciplinary nature of public health and because it seems to correct this imbalance in our system.

Four years ago, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published an article articulating this opportunity and call to action. In it, it called for public health leaders to serve as Chief Health Strategists for their communities in order to address social determinants of health and to ensure the adequacy of built environments and resources in the community to support the health of its citizens. It is a role that is unique to and can best be met through the framework of public health, which integrates and refracts so many different disciplines. At the time this call to action was known as “Public Health 3.0.” I suggest that its application is broader.

It is the future of health. Period.

And it is time to dust off the manual and build back our infrastructure with a view to a more robust, involved, and integrated role for public health.