With the suspension of the rollout and implementation of Medicaid managed care, or Medicaid transformation in North Carolina, it would be easy for providers to tune out related developments from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (Department). However, as North Carolina continues its work to achieve value in Medicaid, it is more important than ever for providers and other stakeholders to follow, engage in, and provide feedback on Department activities. In this article, we will explain developments from the Department and what you need to know, as well as our perspective on the proposals. The Department seeks comments from stakeholders on these new proposals by February 19, 2020.

On January 8, 2020, the Department released two Medicaid Managed Care Policy Papers that advance its design of the value-based payment program and incorporate two new Accountable Care Organization (ACO) models into the overall programmatic strategy for Medicaid Transformation.

It is Atrómitos’ overall assessment that while the value-based payment (VBP) framework is conceptually sound and does not significantly alter what the Department has previously published, the Department sets aggressive timelines and lofty benchmarks upon which they intend to measure the prepaid health plans’ (PHPs) performance. In addition, layering new ACO models and advanced payment methodologies onto the proposed Advanced Medical Home (AMH) program before it has been implemented and tested has the potential to overwhelm and disenfranchise providers and stakeholders who are trying to navigate an already complex system transformation.

Value-Based Payment Strategy

The Department sets forth a five-year strategy for achieving value in the Medicaid system which aligns with the managed care waiver demonstration period approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The policy paper identifies the following strategic objectives:

- Ensure North Carolina Medicaid “purchases health” and is a good steward of state resources

- Establish ambitious but achievable VBP goals

- Recognize market readiness for VBP and align across payers when feasible

- Allow PHPs and providers flexibility in tailoring VBP models to their specific populations and needs

- Build upon and leverage state programs focused on improving high-value care

The Department’s strategy is designed to make the PHPs accountable for driving the adoption of VBP in North Carolina. Therefore, the Department has established targets for PHPs to achieve but leaves broad flexibility for the PHPs and providers to make their own arrangements. As in previous iterations of the Department’s guidance, VBP in North Carolina will be defined using the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP-LAN) Alternative Payment Model (APM) Framework. The HCP-LAN was created to drive alignment in payment approaches across the public and private sectors of the United States health care system and is often the go-to resource for CMS and states when engaging in VBP activities.

VBP TARGETS

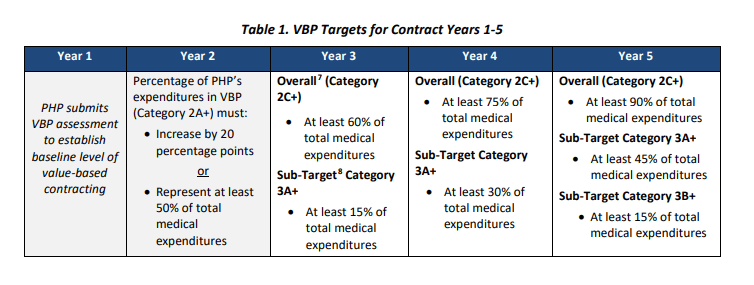

The Department incorporates a range of requirements and incentives to encourage PHPs and providers to enter into value-based arrangements. The requirements are expressed as annual targets and align with the PHP contracts as specified in Section V: Scope of Services of the PHP Contract. The targets (reflected in Table 1) are expressed as the proportion of PHP’s payments to providers that should be governed under VBP arrangements.

For example, the Department expects that at least 90 percent of all PHP medical expenditures be governed by a VBP arrangement by the end of the 5-year period. In addition to the annual overall target, the Department proposes sub-targets that represent the percentage of each PHP’s medical expenditures that must be governed by arrangements in higher HCP-LAN categories (3A+ and 3B+). These higher-level categories reflect arrangements in which providers are accepting increasing levels of risk with 3A+ representing APMs with shared savings (upside risk) and 3B+ APMs with shared savings and downside risk. By year five, the Department expects that over 50 percent of all PHP medical expenditures will be in a risk-sharing arrangement.

The Department designed a “glide-path” to achieve VBP by shifting the targets from lower-level categories (2A+) in early years to higher-level categories (2C+) in the out years of the 5-year period. Starting in contract year 3, arrangements will only qualify as VBP if they incorporate performance-based payments, shared savings and risk, or population-based payments. Additionally, beginning in year 3, targets will transition from measuring an increase-over-baseline to fixed targets of a percentage of total medical expenses.

At the conclusion of each contract year, PHPs will be required to submit a VBP Assessment. The Assessment must document VBP contracts in place and payments made under VBP arrangements. The Department will utilize the results of the VBP Assessment to determine each PHP’s progress on achieving the required targets. PHPs that do not meet the annual targets will be subject to financial withholds in contract year 3.

ATRÓMITOS’ PERSPECTIVE ON NORTH CAROLINA VBP STRATEGY

Department targets are too ambitious. The Department acknowledges that the proposed targets are “ambitious” but believes they “will be achievable given the existing VBP infrastructure, available VBP initiatives and current uptake of these initiatives (such as AMH Tier 3), and the specific commitments of PHPs made in their contracts with the Department.” The existing VBP infrastructure that the Department is referring to is primarily within the state’s Medicare system and is just entering the commercial insurance system in any significant way. While this experience resides within many of the state’s large hospital systems that also participate in Medicaid, it is not widespread and does not easily translate to Medicaid given the significant differences in populations, services, and payment structures between the two programs.

Additionally, the state points to the 1,500 practices that have attested to AMH Tier 3 as evidence of readiness in the system. However, certification as an AMH Tier 3 entity requires only that the practice be capable of assuming primary care management functions. These functions (i.e., risk stratification, care plan development, transitional care management, ADT data, and claims data acceptance) do not directly translate to having the skills, capacity, and systems for managing clinical, financial, and operational performance and risk needed to successfully engage in a VBP arrangement. In fact, at least one large hospital system and a number of smaller independent hospitals and practices downgraded their attestation level once they began the contracting process with PHPs and gained a more meaningful understanding of the requirements.

The Department’s plan lacks the necessary support for providers. While the Department intends to qualify all AMH Tier 3 contracts as VBP arrangements, these contracts will only meet the HCP-LAN Category 2A since the providers will be paid fees to provide care management services. Therefore, without proper support, these providers may be challenged to progress into the higher-level arrangements required in contract years 3-5. The policy guidance does not incorporate any plans for supporting providers and PHPs in meeting these targets. Rather, the Department seeks comment from PHPs and providers on how it can best support the adoption of innovative payment models including the optional models described in the policy paper. In addition to seeking comments from local stakeholders, Atrómitos strongly recommends that the Department engage with other states that have implemented VBP to understand the challenges they have encountered on the road to increasing VBP arrangements and the lessons learned, as it may be difficult for providers who have yet to engage in Medicaid managed care and VBP to know what issues they may encounter or how the State can support them.

Accountable Care Organizations

According to the recently released policy paper, beginning as early as mid-2021 the Department will establish the optional Medicaid ACO program as a key element of its overarching value strategy. Building on the AMH program infrastructure, ACOs will further align incentives to achieve improved health and accountability for the total cost of care (TCoC). What the Department had previously referenced as “AMH Tier 4,” the vehicle for more advanced payment models under managed care, will be replaced by the ACO Program. ACOs under the PHPs are described as having a strong foundation in primary care and being comprised of tightly integrated networks of AMHs, specialists, and other non-AMH providers. The ACO model will provide AMH practices and providers the opportunity to come together to earn shared savings. The Department considered similar design principles as described above when developing the ACO program.

ACO ORGANIZATIONAL REQUIREMENTS AND ATTRIBUTION

A range of criteria for ACOs related to their legal entity status, governance and management, financial solvency, and a minimum number of attributed members will be established by the State and monitored through an ACO certification process. The requirements laid out in the policy paper generally follow the requirements from the 2018 Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) final rule.

The MSSP and other Medicaid ACO models also establish a minimum number of attributed lives for ACO participation. Aligning with the MSSP and other Medicaid ACO programs, the Department proposes that Track 2 ACOs must have at least 5,000 attributed members. The Department is considering setting a lower bar (1,000 – 2,000 attributed members) for Track 1 ACOs in order to encourage participation among smaller independent practices and hospitals.

The number of patients attributed to an ACO is an important factor in managing the associated financial risk of a shared savings arrangement. An individual’s health care needs fluctuate from year to year, often randomly, and if an ACO has too few members, those variations can cause differences between actual and baseline costs that have no reflection on the effort of the ACO. Larger ACO populations help spread risk across a broader group of attributed patients and reduce uncertainty in future medical costs.

Therefore, it is important to understand whether the Department is proposing the minimum attributed lives be at the ACO level or the PHP level. Because the ACOs will be contracted to and paid by each of the five PHPs, if the minimum population size is at the ACO level in practice when calculating TCoC and shared savings the population size will be reduced down to those members who are enrolled with each of the PHPs. Even if the ACO’s population is distributed evenly across the five PHPs, an ACO’s minimum population size of 5,000 becomes 1,000 at the ACO level. In our experience, there are often great disparities in Medicaid managed care enrollment, with one or two plans having the bulk of the population and thus, creating a very real potential for small attributed population sizes which will threaten the viability of both the ACO and the PHP.

Attribution or assignment is a key ACO program methodology used to identify the beneficiaries associated with an ACO and define the population for which the ACO is held accountable. There are two approaches to ACO attribution: prospective and retrospective. The decision on which approach to employ should be informed by assessing the pros and cons of the options with a deep understanding of the quality metrics that will assess performance and impact payment and data.

The Department proposes to attribute Medicaid members to an ACO based on their PCP assignment under managed care. This prospective methodology ensures that ACOs know who their patients are at the beginning of the year and enable them to track and monitor utilization and care needs. While it seems logical that PCP assignment would predict utilization, this approach does not necessarily offer the most accurate accounting of utilization. This is due to the fact that some members will be auto-assigned and utilization and care patterns may change over time as a result of changes in need or other factors.

A retrospective review of claims uses actual utilization data to determine attribution; ensuring only the members that utilized an ACO’s services will be attributed to it. However, retrospective attribution does not enable the ACO to know their population and proactively assess and engage it over the course of the year. It does, however, encourage providers to treat all patients the same.

These are just some of the pros/cons that should be considered when setting the attribution policy. While evaluations of ACO programs suggest there is no one-size-fits-all answer on attribution, it is important for every ACO to understand how each method impacts their financial and quality outcomes. It would therefore benefit stakeholders who are assessing the program if the Department would provide a detailed rationale for proposing a prospective methodology.

CONTRACTING AND OVERSIGHT

PHPs will be required to contract with all ACOs that meet state-established parameters. The State proposes to hold the PHPs responsible for facilitating program participation and conducting oversight to ensure ongoing compliance with program requirements.

In our experience, most of the national Medicaid plans perform the core functions of managed care well (e.g., member enrollment, claims payment, utilization management, data analytics and management, member services, provider services), but when states begin to push additional functions and oversight requirements onto them without any authority to effect change, it spreads their capabilities thin and may result in failed initiatives. This is especially challenging under an ACO model where functions of the ACOs and the PHPs may overlap creating a competitive environment rather than a collaborative one.

We, therefore, caution the state to carefully consider and clearly delineate the functions of the PHPs and ACOs and how they will be required to work together. For example, on page 10 of the ACO policy paper, the Department states it has yet to determine a strategy for how data will be managed across the PHPs and ACOs, indicating that they will release a data strategy prior to the launch of the program. This is a key area of the program that will need to be determined to ensure the success of both the ACOs and the PHPs. The Center for Health Care Strategies has published briefs on these topics and developed resources for state learning collaboratives that stakeholders may wish to review to further understand the challenges of integrating ACOs into managed care.

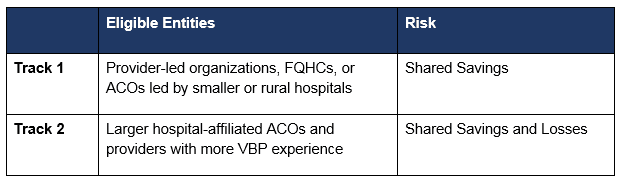

ACO TRACKS

The Department developed two tracks for ACOs to ensure that provider-led organizations, independent and rural providers, and FQHCs in addition to large hospitals can participate in the ACO program. To determine track eligibility the Department modified the Medicare program’s methodology for identifying “percent control over the total cost of care.” The NC methodology will consist of each ACO’s total Medicaid revenue in the previous year as a percentage of the total Medicaid spending on the ACO’s attributed members. This percentage will then be compared to the Department defined threshold. Those above the threshold will be eligible for Track 2, while those under the threshold will be eligible for Track 1. The Department plans to conduct an analysis before setting the specific threshold percentage and is seeking feedback from stakeholders at this time. The Medicare program originally proposed to use 25 percent as its cutoff point, but ultimately determined that 35 percent would increase participation among moderate revenue-producing ACOs.

The NC methodology recognizes that ACOs may differ in the degrees to which they capture attributed patients’ TCoC within their network of participating providers. Therefore, the state has created different expectations for ACOs that represent a smaller percentage of the TCoC.

To encourage early adoption, Track 1 ACOs that join in the first year of the program would be able to participate in an “Early Innovators” program that would offer an opportunity to:

- Weigh in on state policy decisions as an Advisory Group member;

- Participate in learning collaboratives;

- Access enhanced data to inform population health management;

- Receive technical assistance and practice supports; and,

- Bypass administrative requirements such as prior authorization.

Track 2 ACOs that join early would be eligible for a time-limited “glide-path” with more favorable payment terms (similar to Track 1) in years one and two. Those Track 2 ACOs that bypass the “glide-path” payment program and take on full downside risk would also be eligible for the “Early Innovators” program benefits listed above.

ACO PAYMENT

Under both tracks, ACOs will be accountable for the TCoC for all attributed Medicaid members. The Department proposes including nearly all types of Medicaid spending in the TCoC, including physical health, behavioral health, pharmacy, and long-term services and supports. The Department is considering several adjustments to the costs included. The first of these adjustments is related to pharmacy. The Department proposes to price-adjust pharmacy claims to align with the highest value drugs on the preferred drug list in an effort to ensure that variations in the TCoC reflect changes in utilization and not drug pricing. Secondly, the Department proposes to exclude high-cost drugs from the TCoC. In addition to these pharmacy exclusions, the Department plans to exclude voluntary investments in non-Medicaid covered services made by the ACOs in Healthy Opportunities Initiatives. Including such investments in the TCoC would potentially disincentivize the ACOs from making them.

Savings and losses will be calculated by comparing each ACO’s TCoC against the benchmark. The benchmark represents the expected spending for the individual ACO’s attributed members during the contract year. To calculate the benchmark, the Department will establish a uniform methodology.

While there is no detail as to the process for establishing the methodology, the Department is seeking comment on whether to make an adjustment to the historical benchmark to consider regional or statewide average spending or other normative standards. As a stakeholder assessing the program and weighing in on these questions, it is important to know which historical year(s) the state intends to use to set the benchmark. Given the state recognized the regional variation within the program when setting draft Medicaid managed care capitation rates, it would stand to reason that the ACO benchmarks should also reflect any regional variations. If an average benchmark is applied despite significant regional variations, there will be winners and losers on day one of the ACO program, which will have no reflection on the actual effort of the ACO.

According to the policy paper, all ACOs that achieve savings (total spending is less than the benchmark) AND meet ACO quality and health outcome standards will be eligible to receive payments from PHPs for a share of the savings. Track 2 ACOs are at risk for a share of the losses (total spending is more than the benchmark). When the TCoC outpaces the benchmark, the ACO will be required to make payments back to the PHP for its share of the losses.

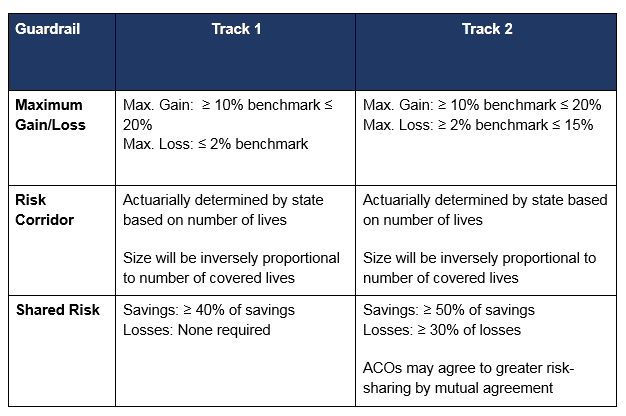

PHPs and ACOs will be permitted to negotiate payment terms to assure each benefit. However, as reflected in the table below, the Department seeks to put guardrails in place to make certain that contracts between PHPs and ACOs reflect the goals of the program and balance the interests of the PHPs and ACOs. ACOs will be protected from excessive risk-sharing through maximum gain/loss provisions by capping savings/losses as a share of the ACOs benchmark. In addition, risk corridors would be put in place to ensure that ACOs only share in savings/losses that are driven by actual outcomes and not just random variance.

These payment parameters were designed to align with the provisions in the MSSP Final Rule.

QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

The Department plans to utilize a variety of payment approaches to tie payment to quality and outcomes in the ACO model, including pay-for-reporting, performance thresholds, and graduated quality scores. In addition to these approaches, PHPs and ACOs will also be given the flexibility to implement other links between health outcomes and payment.

All ACOs will be accountable for a select set of measures that PHPs must report to the Department. To reduce administrative burden and increase the opportunity for program-wide improvement the measures will also be aligned with the AMH and priority measure sets.

The Department also proposes to include population-specific requirements on the ACOs and requests feedback on these initiatives. Typically, the TCoC for the pediatric population is low because children tend to be healthy. Conversely, children with high costs often have long-term complex medical needs. It is, therefore, difficult to achieve savings with either group and consequently, there is little incentive for ACOs to focus on the pediatric population. This is a particularly important point in NC where there is no Medicaid expansion and 70-75 percent of the Medicaid population are children. To ensure that cost alone does not drive ACO efforts, the Department intends to create “gateway” quality metrics that are focused on pediatric care. ACOs that do not meet the state-set benchmarks on these measures will not share in any savings.

The Department seeks input on specific measures that would result in the greatest benefit to the pediatric population as well as other focus areas (e.g. primary care, behavioral health) where “gateway” metrics may be needed to ensure that all populations and providers are being engaged by the ACOs. While, in concept, “gateway” metrics can be used to achieve the Department’s stated goal, in practice, with respect to the pediatric population, there are challenges that are not unique to NC.

In fact, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is doing work to assess these challenges and design approaches to inform the development of a pediatric APM. One of the often-cited challenges associated with pediatric APMs is that there are not sufficient measures available. While the state should continue to track the progress of these efforts, it may be premature to include such measures as a gateway to shared savings.

Finally, because behavioral health is a focus area for Medicaid Transformation, the Department proposes to require the PHPs and ACOs to include payment incentives beyond shared savings that will be available to providers that successfully integrate physical and behavioral health. The PHPs and ACOs will be granted the flexibility to design these incentives and selects measures that will support their behavioral health initiatives.

ATROMITOS’ PERSPECTIVE ON NC ACOS

The Department must reevaluate comparing North Carolina’s program to more established Transformation states. If, like us, you follow what is going on in Medicaid across the country, you know that North Carolina is not proposing anything outside of the box. Many states have operationalized VBP strategies (25 states) and ACO programs (22 states). While only half are running them concurrently (12 states), we can confidently say that no other state has built and implemented ACOs, VBP, and managed care from the ground up at one time.

On the contrary, when you look at the three states the Department referenced on page 8 of the VBP policy paper (Washington, Massachusetts, and New York), you will find that these are some of the most mature managed care states in the country — each having engaged in large-scale implementations of managed care in the 1990s. While these states are also amid significant Medicaid transformations that are incorporating many of the initiatives North Carolina is considering, they are building these programs upon 25+-year-old well-tested and stable managed care environments. That’s just not the case for North Carolina.

A state that is more similarly positioned to North Carolina is Iowa, which implemented Medicaid managed care for the first time just a few years ago. Iowa also imposed aggressive targets for achieving greater levels of VBP. However, the implementation of Medicaid managed care has not gone well in Iowa. Plans have left the market and at least one MCO is currently subject to significant financial penalties for failure to appropriately pay providers. There are likely valuable lessons learned from Iowa, as well as Washington, Massachusetts, and New York.

While the Department intentionally aligned the proposed Medicaid ACO model with the Medicare ACO model, it should not assume wide participation among existing ACOs in the Medicaid model. The majority of the ACO policy proposed in the Department’s paper is closely tied to the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and reflects a national trend towards aligning Medicaid ACO strategy with their Medicare counterparts. Given the experience and results that ACOs have had with the MSSP across the country and within North Carolina, it makes sense to start there and to allow existing ACOs to leverage their expertise and programming. But operationalizing these policies within the North Carolina Medicaid environment is where the rubber meets the road and where the ACO program will either succeed or fail. With the advent of the CMS Direct Contracting Model and other significant changes to Medicare’s established ACO programs, we anticipate that most ACOs will be focused on making the adjustments needed to meet CMS’ new expectations. Therefore, making it unlikely that ACOs are going to shift resources to focus on establishing a Medicaid ACO—even if there is alignment with the Medicare program.

The Department should pause and map out a reasonable timeline and strategy for the development of the ACO program. All of this is to say that the Department is taking on a lot and putting even more on the shoulders of the PHPs and the providers to be ready for and ensure the success of this massive transformation. Yet in the eleventh hour, the Department is adding a significant component to the transformation and building it on top of an untested AMH program. While transformations are meant to enact systematic change, there is also something to be said for allowing a system change, reacting to the change, and making adjustments before throwing more at it.

We know from every other state’s implementation of Medicaid managed care that there will be bumps in the road, some big and some small. But it will take a coordinated and collaborative effort on the part of the state, the PHPs, and the providers to quickly identify and address these issues to minimize disruption to the members and the system. This can be a full-time job for the first year or two of a program. So while the Department has proposed a number of components of an ACO model built on existing model designs, as we noted, it will be critical that the model is customized for NC.

This should and will take time and include meaningful stakeholder engagement, but the proposed mid-2021 start date suggests this development activity will be happening in the midst of go-live. To protect the integrity of the Medicaid program and see it through this Transformation thereby bringing value to North Carolina, we strongly recommend that the Department take a long hard pause and map out a reasonable timeline and strategy for the development of the ACO Program.