If you want to understand how any system works – follow the money. That is why last month, we kicked off a limited series on the topic of Medicaid State Directed Payments. In our first article— State Directed Payments: Part I—Medicaid Financing 101— I introduced some of the nuts and bolts of Medicaid financing and administration. With that background today we will discuss some of the more complex constructs of Medicaid financing that states can choose from to leverage federal funding and direct MCOs to increase payments to select providers.

Today’s article will focus on Medicaid Supplemental Payments—namely the Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Program and the Upper Payment Limit (UPL) Program. Additionally, I will provide a brief description of the State Directed Payment option laid out by CMS. These payment options are crucial to understanding Medicaid financing because they represent more than 25 percent of payments to key Medicaid providers (i.e., hospitals and nursing facilities). We will then review insights from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) analyses on the use of state directed payments.

Supplemental Payment Programs: Providing Additional Funding Flexibility

Medicaid payments to hospitals and other providers play an important role in these providers’ finances, which can ultimately affect beneficiaries’ access to care. States have a great deal of discretion to set Medicaid payment rates for hospitals and other providers. Medicaid payments have historically been (on average) below costs, resulting in payment shortfalls. It has been estimated that Medicaid payments to hospitals accounted for 88 percent of the costs of patient care in 2020, while Medicare paid 84 percent of costs. While some of this shortfall is made up by the overpayments that hospitals receive from patients with commercial insurance; those hospitals that serve a disproportionately large percentage of Medicaid patients are unable to recoup costs from their smaller commercially insured population.

Most states pay hospitals a “base rate” set by the state Medicaid agency. Base rates often do not reflect charges or costs for services and are typically set as a statewide or hospital group rate. Often, these rates are insufficient to cover costs which as noted above has a greater impact on providers that serve a large percentage of Medicaid patients. As such, federal regulation has granted states the flexibility to target additional funding to these institutions—these targeted funds are referred to as supplemental payments. States target funding using state-defined criteria that sometimes, but not always, include Medicaid days, visits, or discharges.

As covered in our last piece, in general, states are not permitted to direct the expenditures of a Medicaid managed care plan under the contract between the state and the plan or to make payments to providers for services covered under the contract between the state and the plan (42 C.F.R. §§ 438.6 and 438.60). The reason being that if rates paid to managed care companies for services are actuarially sound (which they are required to be under 42 C.F.R. § 438.4) then there should be no reason for the plans or providers to need additional payments for these services.

Of course, maintaining network adequacy and the availability of services and infrastructure across a state with diverse population distribution and resources complicates this actuarial calculation. And while Medicaid is an insurance program concerned with the payment of services, the state is also responsible for maintaining the integrity of its public health infrastructure. That includes the viability and maintenance of hospitals, nursing facilities, and other facilities.

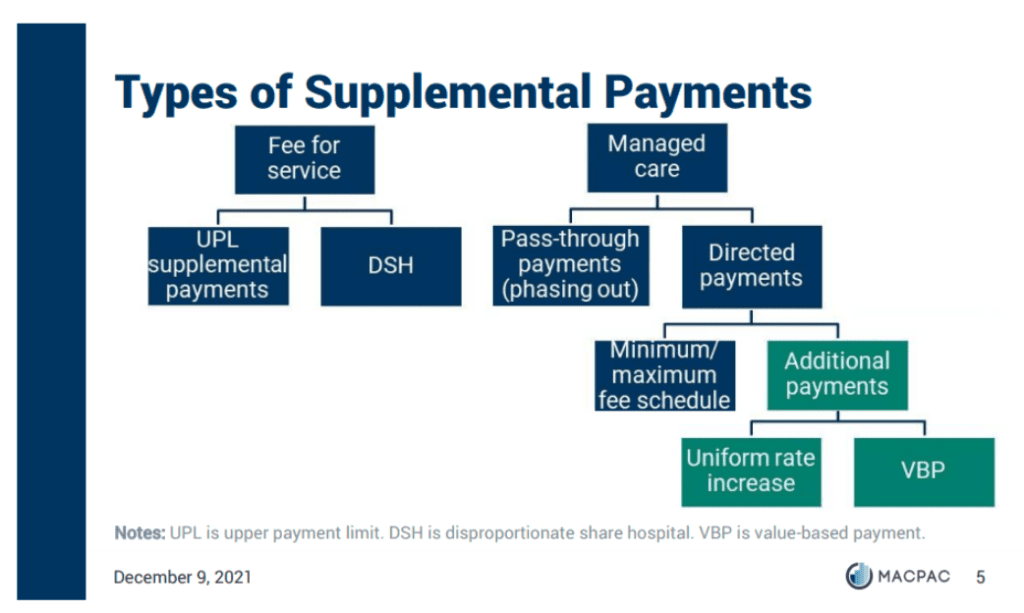

Supplemental payment programs provide an exception to this general rule prohibiting direction of payments. This exception has allowed states to direct funds to specific classes of Medicaid providers above what the state pays for individual services through Medicaid rates. The rationale being that supplemental payments enable states to meet other policy and public infrastructure needs, namely, to offset low Medicaid payments for services or to support safety-net providers. Supplemental payments fall into two categories:

- Disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments. Medicaid DSH payments are statutorily required payments intended to offset hospitals’ uncompensated care costs to improve access for Medicaid and uninsured patients as well as the financial stability of safety-net hospitals. DSH payments are reserved only for those hospitals that serve a significantly disproportionate number of Medicaid and uninsured patients. In fiscal year (FY) 2020, Medicaid made a total of $19.5 billion in DSH payments.

- UPL (upper payment limit) payments. Medicaid UPL payments are supplemental payments to hospitals, nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities for persons with intellectual disabilities (ICFs/ID), and freestanding non-hospital clinics that are intended to make the difference between Medicaid payments and the amount that Medicare would have paid for the same service for hospitals serving large numbers of Medicaid and uninsured patients. Medicare reimbursement rates are often used as a benchmark for provider payments. UPLs are restricted to fee-for-service (FFS) payments. In fiscal year (FY) 2019, 32 states made a total of $19.1 billion in UPL supplemental payments to providers. UPL payments represented approximately 25% of total national Medicaid hospital expenditures in 2019.

It is important to note that while supplemental payments are intended to make up for shortfalls, there are no provider specific limits; therefore, individual providers may receive more than their reported Medicaid costs if the aggregate payments to all providers in their class do not exceed the aggregate UPL.

As states have transitioned from FFS payments to managed care, available FFS UPLs are decreasing because UPLs are restricted to FFS payments. The shift to managed care while beneficial in many ways has therefore made it difficult for states to ensure consistent funding levels for these select provider types. For this reason, some states have excluded certain services or populations from managed care (to preserve such payments) or sought Section 1115 demonstration waiver authority to continue making supplemental payments under managed care arrangements.

“Creative” Accounting: Passthroughs and Directed Payments

Prior to 2016, a small number of states offset the loss of FFS supplemental payments by increasing capitation rates paid to managed care organizations (MCOs) and requiring MCOs to direct these additional funds to designated providers. This mandated payment structure, known as pass-through payments, was typically not tied to the delivery of services and was often financed by providers through intergovernmental transfers (IGTs) or provider taxes.

MEDICAID PROVIDER TAXES:

HOW THEY INCREASE OVERALL MEDICAID FUNDING TO STATES

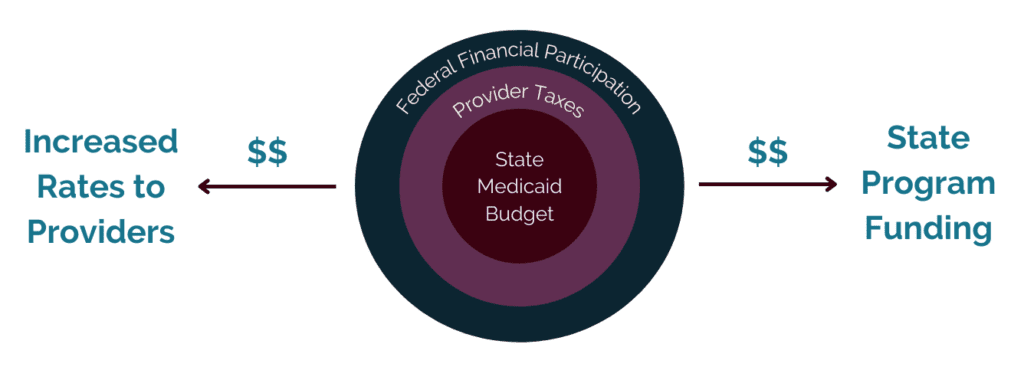

Almost every state in the US has a provider tax and some have 3+. Medicaid provider taxes play a significant role in managing the impact of Medicaid funding on state budgets and increasing overall Medicaid program funding available to the state. Many states have implemented a tax/assessment specifically for hospitals; others have provider taxes for nursing homes, managed care plans, surgical centers, and other health care facilities.

Take for example a small state, with a Medicaid budget of $100, plus the federal matching rate. The federal matching rate for this fictional state is 50 percent, so the states total Medicaid budget is $200. The state is looking for a way to increase their $200 budget due to rising Medicaid expenses. So the state levies a 5 percent tax on all of its hospitals’ patient revenue, totaling $50 in incurred taxes sent to the Medicaid program and added to the available State Medicaid funds.

Since the state receives a 50 percent match on all state Medicaid funds, the new tax revenue totals $100 in new Medicaid funds ($50 from the state provider tax and $50 in federal match) – increasing the Medicaid budget to $300. The state then returns a portion of the tax levied to the hospitals through increased rates and uses the remainder of the new money to help fund its Medicaid program.

If this sounds like a “legal” money laundering scheme to you… you aren’t alone in this thinking.

In the Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule published in 2016, CMS noted its concerns with pass-through payments and clarified that supplemental payments in managed care are not actuarily sound. Specifically, they identified the following issues:

- Medicaid only provides statutory authority for managed care payments to be made to providers when directly related to the delivery of services under the contract.

- These payments limit the managed care plan’s ability to effectively manage care delivery and implement value-based purchasing strategies and quality initiatives. When payments are delinked from specific services rendered to patients, they may in fact undermine value-based purchasing.

As a result, CMS made significant policy changes in this area requiring states to phase out the use of pass-through payments within 10 years. While the rule allows states to continue to use Section 1115 demonstration waivers to make supplemental payments to some providers (e.g., delivery system reform incentive payments (DSRIP)), CMS does not plan to renew existing DSRIP demonstrates and has encouraged states to develop plans to sustain the progress through value-based payment strategies.

In its place, CMS created a new option for states to direct payments to providers under certain conditions. Specifically, CMS requires that directed payments be:

- tied to utilization and delivery of services,

- be distributed equally to specified providers under the managed care contract,

- advance at least one goal in the state’s managed care quality strategy, and

- not be conditioned on provider participation in intergovernmental transfer (IGT) agreements (42 CFR § 438.6(c)).

Under this option, directed payment arrangements are categorized into two broad categories:

- State-directed (minimum/maximum) fee schedules or uniform dollar/percentage increases in payment above negotiated capitated rates. The state may propose to use an approved state plan fee schedule, a Medicare fee schedule, or an alternative fee schedule established by the state.

- Value-based purchasing directed payment arrangements. These payments require participation in specified VBP initiatives (i.e., pay-for-performance incentives or shared-savings arrangements for accountable care organizations). Alternatively, states may also design their own VBP models.

It should be noted that regulations allow MCOs to adopt state plan payment rates or implement VBP through provider contracting. States do not have to have a directed payment arrangement for MCOs to elect to engage in such provider payment strategies.

The process of application for and approval of directed payments is similar to that of Medicaid state plan amendments. However, unlike approved state plan amendments, CMS has not made approved directed payment arrangements publicly available. While states must incorporate the directed payment arrangement into their MCO contracts and capitation rates; details of actual spending on directed payments are not publicly available.

Evaluation of Directed Payments

MACPAC’s Principal Analyst, Rob Nelb, reported at the April 2022 MACPAC Commission meeting that use and spending on state directed payments has rapidly grown from 65 arrangements in August 2018 to more than 200 in December 2020. While spending information is lacking (due to the lack of publicly available information noted above) for over half of the approved arrangements, MACPAC found that of the 96 arrangements with estimates projected spending was more than $25 billion. This is larger than spending on DSH ($19.7 billion) or UPL supplemental payments ($19.1 billion) in FY 2019.

Because there is no limit on directed payments, it is expected that these payment amounts will continue to grow. Additionally, it is important to note that while some states are using directed payments to preserve prior supplemental payments, states are increasingly using directed payments to make new supplemental payments.

TYPES OF ARRANGEMENTS

MACPAC’s analysis of directed payment arrangements used the CMS application form to categorize the types of arrangements (state directed fee schedules or value-based purchasing directed payment arrangements). While there are inconsistencies and challenges with the CMS data the following findings were made about the types of directed payments being approved:

Almost two-thirds of arrangements adjust base rates by establishing a minimum fee schedule; however, these arrangements only account for 4% of spending

- Most direct payment spending (80%) is for uniform rate increases

- Only 16% of direct payment spending is tied to VBP. The breakdown of VBP is as follows:

- Pay-for-performance 42%

- Population-based payment 24%

- Bundled payment 7%

- Other 31%

Meaning that most states are using directed payment arrangements to require contracted MCOs to establish minimum fee schedules for provider payment using the Medicaid state plan fee schedule or the Medicare fee schedule. However, most direct payment spending increases are tied to a required uniform dollar amount increase in payments to providers. These data points suggest that further analysis may be warranted to understand the implications of these additional payments which represent 96% of total direct payment spending. Specifically, those that require a uniform rate increase which is akin to a lump sum supplemental payment in FFS.

Directed payments that simply put more money in the hands of providers without any assessment of the quality of the services being delivered will only further inhibit the healthcare system’s move to value-based payment. Additionally, such mandates make it difficult for MCOs to effectively manage their provider networks. As MCOs utilize rate and contract negotiations to ensure that their provider networks are meeting standards and quality outcomes for their patient population, taking this authority away from the MCOs is counterintuitive to the managed care model.

Nelb reported that the CMS application categories did not capture the full array of payment types; therefore, some payment types did not fit neatly into the reported categories. Notably, there was a small subset of arrangements that MACPAC found make very large additional payments to providers – increasing payments by more than $100 million a year. This subset of 35 payment arrangements accounted for over 90% of total projected direct payment spending. Most of the arrangements in this small subset were targeted to hospitals and hospital systems that were being financed by IGTs or provider taxes. And in these arrangements, the hospitals were being paid above the Medicare rate, which is the limit for payments in FFS arrangements.

PROVIDERS TARGETED

MACPAC found that 43 percent of directed payment arrangements were targeted to hospitals. Other provider types targeted included physicians, mental health providers (institutions and practitioners), and nursing facilities.

FINANCING

Most of the approved directed payments are being financed by provider taxes (15%) and IGTs (20%). This likely is an influencing factor as to the types of providers that states are targeting. Payments are being targeted to those providers who can be taxed or that can participate in IGTs and thus contribute to the non-federal share of Medicaid payments. Most of the VBP directed payment arrangements (62%) were financed with state general funds.

QUALITY GOALS

While states articulated a variety of quality goals (e.g., increased care coordination and integrated delivery systems, decreased cost, and increased community-based care delivery) as the intent for their state directed payments, findings indicate that the most common reason for the adoption of state directed payments (particularly uniform rate increases) is to improve access to care for a given service. However, it is unclear whether there have been meaningful improvements above what is already required under managed care network adequacy requirements because CMS does not monitor states for their achievement of quality goals once the payment arrangement has been approved.

While Medicaid supplemental payments are primarily paid to hospitals and other institutional providers, it is critical that all Medicaid stakeholders understand the various components of Medicaid payments. As we discussed, these flexible payment strategies enable states to increase state Medicaid budgets and target funding to key safety net providers. Regulatory changes made by CMS in 2016 to phase out pass-through payments in favor of directed payments were intended to ensure greater alignment with state quality programs and value-based payment strategies. However, analysis indicates there are gaps in the information available to understand the implications of such policy changes. And at the pace these payments are growing, left unchecked these funding mechanisms may have a sizeable impact on the overall Medicaid budget at both the state and federal level. Therefore, as directed payments continue to increase in size and states dedicate larger portions of their budgets to funding these payments, it is incumbent on us all to ensure that there is adequate transparency and oversight of the program.

Next month, in my final article of the series, following the release of MACPAC’s June 2022 Report to Congress, I will summarize the concerns that have been raised by MACPAC about the lack of transparency and oversight of the directed payments program, highlighting states with directed payments that have been used to significantly increase funding to select provider groups. Additionally, I will review the recommendations that MACPAC makes to Congress on how to improve the program and include my perspective on the impact of such recommendations to Medicaid stakeholders in states across the country.