Last month JAMA Open published a Research Letter evaluating the impact of the CURES Act (which requires immediate release of test results to patient portals) on utilization of patient portals, physician inboxes, and workflow processing. Comparison of utilization rates by patients at Vanderbilt University Medical Center before and after implementation indicates increased use of portals alongside a two-fold rise in resulting emails to physicians within 6 hours of review of the results. The Letter opens discussion on concerns of burnout among physicians due to the increased workload and questions whether this increase in patient emails indicates increased confusion among patients regarding health care communications.

The Letter acknowledges that the CURES Act and the resulting regulation represents “a marked transformation in patients’ opportunity to take ownership of their health care.” But questions whether this benefit is “overshadowed by unintended consequences to patient well-being and clinical workload.”

To understand the problem more fully and evaluate the merit of this criticism, we need to back up and dig deep into analyzing the context and application of the CURES Act. And we will do that, but first, let me share my initial, unvarnished reaction.

How to put this?

If you, like me, spend any (or way too much) time on Social Media, you have likely come across the “I understood the Assignment” reels on TikTok or Instagram. These reels (with background audio of Tay Money’s music to the same name) show someone is killing it, giving something 100% percent and reaping the rewards – because they understood the assignment and worked to the test. In short, the output (result) aligns with the individual’s intentional inputs.

So, let’s just say that, as I read this Research Letter and the coverage of the study, I had the image of well-heeled and buttoned up ONC and CMS regulators jamming to this music when learning about the results of compliance with ONC’s interoperability regulations, because, errrr…they understood the assignment.

Having given that preview on where this article is going (and my very balanced and non-opinionated take) (please tell me you hear my sarcasm and self-knowledge), let’s back up and break it down. The following sections provide a little more context as to what the CURES Act did and get a lay of the land related to data exchanges and the release of test results before this legislation.

WHAT THE CURES ACT DID

The CURES Act prohibits the practice of Information Blocking. Information Blocking is a practice by a provider, health IT developer, or Health Information Exchange, that is “likely to interfere with access, exchange or use of electronic health information” and is not otherwise excepted by law or regulation as a reasonable and necessary activity. This broad definition covers much ground (and the majority of the time between the passage of the CURES Act in 2016 until implementation by CMS and ONC’s final Interoperability rules this year was spent on this very issue). While these five years in rulemaking have provided important guidelines and parameters to identifying Information Blocking, it still comes down to a case-by-case assessment that is best summed up by the “know it when you see it” test. However, one area that DHHS has been clear on is the communication of lab or other test results. The agency outlined in its published FAQ that adopting an organization-wide policy that systematically delays the release of lab results or other tests to ensure that the ordering clinician first reviews the results or a policy that those results are only communicated to the patient by the clinician would likely be interference, and therefore information blocking.

Delaying test results to enable review and communication by a clinician is ubiquitous. Part of the rationale for this practice is ensuring that test results are not misinterpreted but instead communicated in a manner that provides the patient with the context necessary to understand the result and next steps.

BACK TO THE ARTICLE

So with that setup – let’s turn back to the evaluation conducted at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

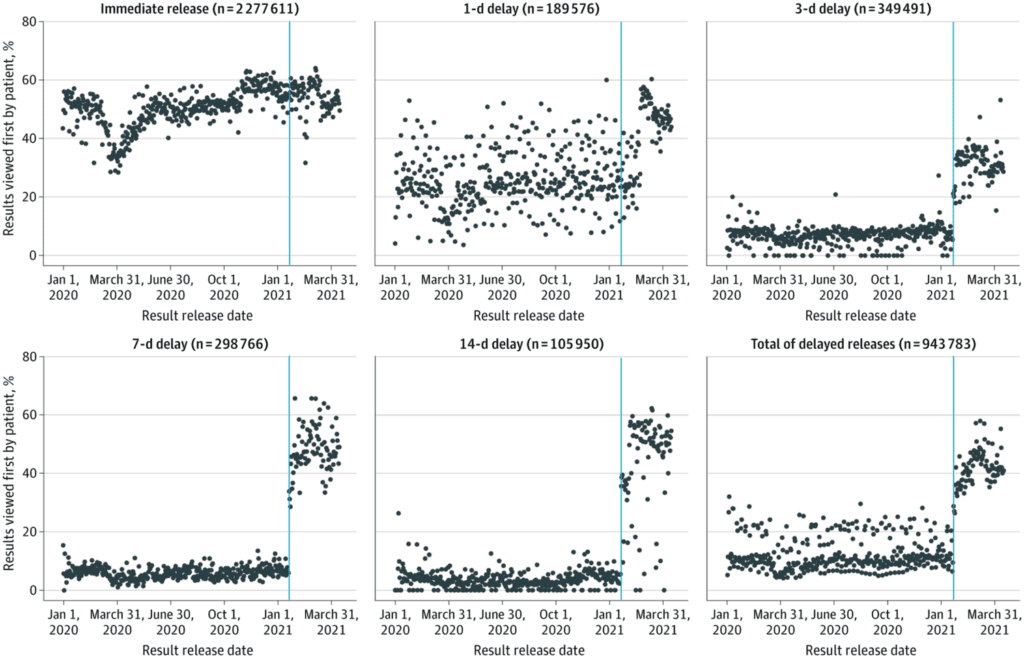

The Researchers looked at all health results released through the patient portal between January 1, 2020, and April 16, 2021. Before implementing this requirement, providers released test results on a tiered schedule based on the information’s complexity or sensitivity. In addition to those results that were released immediately to patients (defined as being available to patients at the same time the results are available to the ordering clinician), results could be on a delayed-release, falling into a schedule of 1) 1-day delay; (2) 3-day delay; (3) 7-day delay and (4) 14-day delay.

(Pause)

Let me give you a minute to digest that last category (because I think it deserves a call out). I find it hard to justify a fourteen-day delay in providing test results to a patient portal.

But to return to the evaluation.

Before compliance with the CURES Act (January 20, 2021), only 10.4% of patients accessed and reviewed test results through the portal before a clinician first evaluated the results. After the immediate release of all test results, that rate of review by patients before clinical review jumped to 40.3%. That is pretty significant.

The question is whether that is a bad thing – whether patients’ access to test results without the benefit of clinician interpretation or delivery of their health data translates to confusion or (avoidable) distress. The researchers attempted to measure this impact by evaluating the number of patients who then reached out to their provider within 6 hours of review of results. The study identified a two-fold increase in this outreach by patients.

But isn’t this what we want to happen? Patients actively reach out to and engage with their care team and take ownership of their health data and care plan? That sounds like exactly the objective we’ve all been talking about when we talk about patient-centered care. There will always be an asymmetry in information between providers and patients when it comes to interpreting and contextualizing health information, but is that a reason to perpetuate the structural hierarchy (and paternalism) that has plagued healthcare?

I think not. And I applaud how the CURES Act forces structural changes that challenge this dynamic.

ADDRESSING PHYSICIAN BURNOUT – IT’S REAL.

I want to stress that I do not underestimate or undervalue the real burden of this increase in EHR messaging to the care team, particularly physicians. EHR workflow management (specifically responding to messages from patients and members of the care team) is a significant part of a clinician’s workflow and is directly associated with self-reported burnout.

But I have the sneaky suspicion that holding up EHR message workflow management is as much a proxy (and a helpful strawman) for more significant problems where providers are required to do more with less, for more people. WE have created an unsustainable (and I would suggest bordering on exploitative) environment for our providers. The conditions that providers work in are the leading drivers of dissatisfaction and burnout are the working conditions themselves. As we recently observed, it is a problem “when the hardest part of one’s job [as a provider]…is that one consistently doesn’t have enough time to do the job.”

But that doesn’t mean that patient access to information when it is available should stop – but rather, the broader conditions need to be addressed.

Changing a system – particularly such a revolutionary recalibration based upon a patient’s right to their own data – is messy, painful, and full of what the article’s authors very diplomatically phrase as “unintended implications.” That doesn’t mean that we don’t do it.

Instead, the question is “What next”? Now that we have this input on the (evident) effectiveness of the recent regulations – how do we (and the system) adapt?

I suggest, instead, that this underscores the importance of utilizing (and investing in) a more collaborative care or team-based model. Where there is a care team model structure in place, it may encourage actively empowering other care team members to take a more prominent or autonomous role (necessity is the mother of invention – and adaptation).

That is our next mission, should we choose to accept it.