A few decades ago, we may have never expected that the typical American would not be able to afford housing.

In 1989, Homer Simpson supported his family on a single income as a safety inspector at a nuclear power plant. The family can afford a four-bedroom home within skateboarding distance to downtown, two cars, two pets, and three children. At the time, nobody found this strange or unusual at all. Today, however, this American Dream is unattainable for most Americans.

Permanent, safe, and stable housing is increasingly out of reach for millions of Americans, and the impact is more than economics. It’s impacting the health of our communities, and the burden is shouldered by the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) community. Housing is a key to wealth and health; whether renting or owning, the effects of housing affordability can last for generations.

A REVIEW OF THE SUMMER HOUSING MARKET

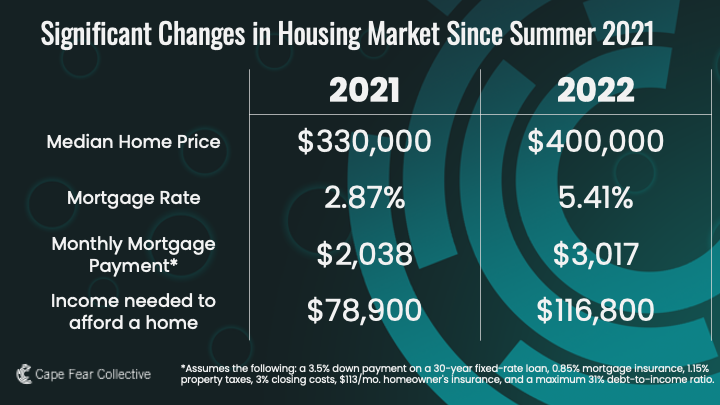

In summer 2022, the median price for a home sold in the Coastal Cape Fear Region was $400,000 (according to realtor.com), a 20% increase from last summer. At the same time, average 30-year mortgage interest rates were up over two percentage points, nearly doubling from 2.87% in July 2021 to 5.41% in July of 2022. This seemingly small increase means big changes for everyone except cash buyers. A potential home buyer taking out a 30-year mortgage on the median priced home in July 2022 would see a monthly mortgage payment of about $3,000* after adding taxes, insurance, and mortgage insurance.

Up 50% from last year, this means that the annual income needed to afford that home went from about $79,000 to $116,000 in a single year. With an annual income of only $60,000, this leave the median household unable to afford the median home.

Homeowners are not the only ones feeling the burden of these market changes, as median rent has increased between 10% and 20% at a time when roughly half of all renters were already cost burdened. Renting is becoming the default mode of housing, with housing costs forcing lower income households further away from job centers.

Across the country we are facing a housing shortage, which drives up prices for new homes and rentals. During the pandemic, we have seen how fragile many of our systems are and housing is no exception.

Decades of wage stagnation, declining purchasing power, and the increasing price-to-income ratio of housing will keep prices high. Prices may come down in the short term, but the long term trend is that the cost of housing is increasing.

Half a century of trends are pointing in the wrong direction, and that impacts more than just a household’s bottom line.

THE RENT EATS FIRST

Having a roof over your head is so critical to an individual’s safety and comfort, that many people find themselves in the difficult position of sacrificing other expenses to maintain housing. Car repair, education, preventative medical treatment, and even food take a back seat to the rent payment.

Even when housing IS secure, a myriad of health risks can be found within the home. Households who are cost-burdened (meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing costs) are often unable to address issues directly related to chronic health outcomes, such as mold, lead paint, pest infestation, fire risks based on poor code compliance, and pollution. Cutting services like heating and air conditioning are popular money-saving practices which can put people, especially children and the elderly, at greater health risk.

Suburban sprawl and lack of infrastructure has limited the connections people have to jobs, services, schools, and community. When we build bigger roads, bigger suburbs, and bigger department stores, it is imperative we start to consider the impact to public health. For example, living near high-volume roads increases rates of respiratory diseases and sedentary lifestyles increase risk for cardiovascular disease. In contrast, the benefits of walking every day to work or for errands cannot be understated. Having timely and frequent public transportation, proximity to nutritious groceries, and safe exercise space all correlate with improved public health.

In addition to physical health outcomes, research is only now beginning to quantify the connection between the trauma of homelessness and unstable housing to mental health, substance abuse, and suicide. Especially for young children, Housing IS healthcare.

WHAT CAN WE DO

Those working in healthcare must be ready to directly address the problems stemming from housing insecurity and unaffordability. This is true now more than ever for health systems serving lower income and BIPOC customers. Black home ownership is lower now than before the Civil Rights Act. American Indian and Alaska Native households have higher rates of physical housing problems in tribal areas. Every community has its own unique challenges and needs.

We have the tools and power to change the health of tomorrow. When we expand our idea of what health means, we find new and unique ways to improve it. Measure your impact, disaggregate your data, turn insights into action, and hold yourself accountable just as much as you do your elected officials. As a society we must have some tough conversations centered on data, as we all have a part to play in shaping our future.

*Assumes the following: a 3.5% down payment on a 30-year fixed-rate loan, 0.85% mortgage insurance, 1.15% property taxes, 3% closing costs, $113/mo. homeowner’s insurance, and a maximum 31% debt-to-income ratio.