In a recent article, we raised the question of whether nonprofit hospitals are effectively “earning” their privileged tax status by returning a community benefit greater than, or at least equal to, the cost of their deferred taxes. We also discussed how the Affordable Care Act provided essential tools, the Community Health Needs Assessment and the Community Health Improvement Plan, for defining and measuring the “community benefit” created by the Hospital. This requirement was the first time the community benefit standard explicitly tied nonprofit hospital operations to the public health principle of community health improvement.

This week, we will continue our scrutiny, narrowing in on an issue that has been the subject of decades of Congressional inquiries and public debate: how the financial operations and, more specifically, the collection practices of nonprofit hospitals align with their nonprofit status and privileges. We’re talking (among other things) about medical debt and aggressive debt collection practices.

Scrutiny Leading up to the ACA

In the years leading up to the ACA, there were numerous media stories on the practices used by hospitals nationwide to collect unpaid bills from patients. From charging excess interest on unpaid bills (thereby making it harder for patients to pay off the bills) to patients being sent to collection agencies that harassed them to being sued or sent to jail (yes, sent to jail) because of unpaid medical bills, a process called a “body attachment.” Hospitals often failed to follow their policies for free or discounted care. This means that they pursued individuals with low incomes, often without insurance or underinsured. Lack of transparency and consistency for hospital charity care policies meant that individuals had limited or no means of recourse or appeal.

To get an idea of the prevalence and impact of this kind of aggressive debt collection practices across the nonprofit hospital industry before the passage of the ACA, it is worth looking back on a few headlines:

- Minnesota sues Allina Health System over medical debt interest (The state attorney general pursued the nonprofit health system for imposing illegally high-interest rates (18%) on medical debt. The State and the health system subsequently settled, with Allina agreeing to reimburse over a million dollars to patients.)

- Advocate Health to refund $3.5M to settle suit (The largest health system in Illinois settled a class action lawsuit alleging overcharging uninsured patients, impacting an estimated 40,000 patients over ten years.)

- Imagine getting sick, getting bills you can’t pay, then being sent to jail (An article outlining the practice of body attachment, where individuals with outstanding debts are arrested and imprisoned.)

Members of Congress held hearings and engaged in other investigations to understand and obtain needed explanations for why nonprofit hospitals that receive substantial tax exemptions to benefit their communities would engage in such practices.

ACA Financial Assistance, Billing, and Collections Requirements

The ACA, a significant legislation intended to reform the U.S. healthcare system, was an excellent vehicle to address public and congressional concerns about hospitals’ aggressive debt collection policies. It introduced requirements for nonprofit hospitals mandating the creation, publication, and adherence to policies regarding:

- Financial assistance and charity care,

- Assuring the delivery of emergency medical care regardless of ability to pay and

- The imposition of limitations on charges made to uninsured individuals.

Finally, it imposed clear limits on hospital collection actions, imposing a duty on the hospital to make reasonable efforts to determine if a patient is eligible for financial assistance before pursuing “extraordinary” collection practices.

It did this in four ways, illustrated in the table below:

| Financial Assistance Policy (“FAP”) Required | Policy must be written in plain language, be widely publicized and include: · eligibility criteria for financial assistance and the assistance (free or discounted) available based on criteria · methodology for calculating charges to patients · the process to apply for financial assistance · the actions that may be taken in the event of nonpayment identification of all related providers and practices to which the policy applies. |

| Emergency Medical Care Policy Required | Hospitals must have a written policy requiring the delivery of any emergency medical care, regardless of a patient’s ability to pay, as defined by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). This policy must prohibit actions that would discourage individuals from seeking emergency care (e.g.: requiring prepayment in an Emergency Department, or engaging in debt collection activities on facility premises). |

| Limitations on Charges Imposed | Charges to uninsured or underinsured individuals for medically necessary care must be limited to the Amount(s) Generally Billed (“AGB”) to insured patients. Hospitals can use a “lookback” method to determine, AGB, but must use only one of three approved methods. |

| Billing and Collection Practices Restricted | Hospitals must make reasonable efforts to determine whether an individual is eligible for financial assistance prior to pursuing extraordinary collection activities (ECA). Deferral, denial, or requiring prepayment of additional medical services based on an existing debt constitutes an ECA. Requiring prepayment or a deposit can be tantamount to denial of care. Hospitals that sell debts or pass on to a third-party collection agency are responsible for the collection practices of the collector. |

“It’s All Just a Bit of History Repeating”*

The financial policies and collection practice restrictions created by the ACA were critical. You would be excused if, given where we are in this article, you thought this was just a retrospective, a case of “look how bad it used to be” and celebrating the impact and importance of the ACA. Unfortunately, while the widespread trend of the most egregious practices was, for a time, constrained, we are pretty much back where we started. It’s all just a bit of history repeating.

In August, in a rare example of actual bipartisan action, Senators Warren, Warnock, Cassidy, and Grassley sent letters to the IRS and Treasury expressing concern about reports of tax-exempt hospitals across the country engaging in “practices that are not in the best interest of the patient” and that “allowed some nonprofit hospitals to avoid providing essential care in the community for those who need it most.” In these letters, the Senators urged the IRS to investigate the “overly broad” language defining community benefit and the impact on care and costs. The Senators also requested information from the IRS on enforcement actions taken by the agency, including the revocation of hospital tax-exempt status since 2014, when the ACA requirements went into full effect.

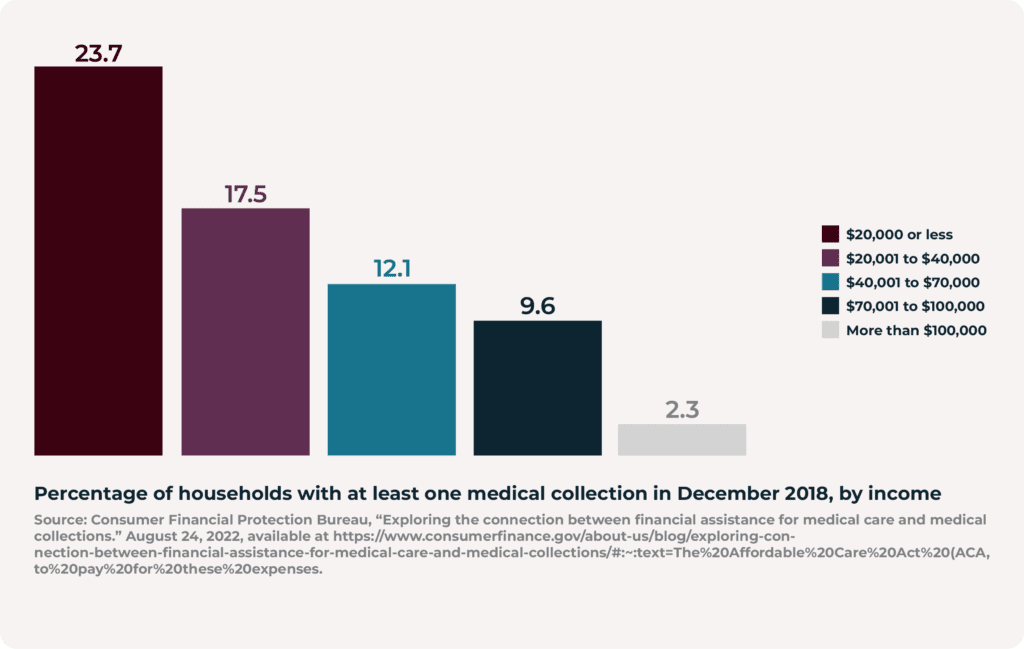

They were correct to be concerned. Incidence of medical debt is back on the rise – and the poorest members of society, those who, by any calculation, would be eligible for charity care under the required financial assistance policies, bear the lion’s share of the burden. An analysis by the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that 27.3% of households with an annual income of $20,000 or less had at least one medical debt in collection in 2018. Low-income households with children are most likely to have medical debt in collection; in 2018, 38.1% of households with children and an annual income of less than $40,000 carried medical debt. As the report concludes, many, if not most, of these individuals in collections would be eligible for financial assistance, assuming the qualifying criteria is set at 200% of the Federal Poverty line. And the situation is worse now than in 2018, given that the poverty rate increased in 2022 for the first time in over a decade.

It isn’t only a question of failing to identify individuals eligible for charity care but also the aggressive practices that nonprofit hospitals continue to use to pursue payment. A 2022 New York Times article reported that the Providence chain of hospitals had not only spent under the average 2% of their expenses on charity care by 50% but had begun shaking down patients (there really is no other way to describe it) for payment – even though they qualified for charity care. Washington State Attorney General Ferguson filed a consumer protection lawsuit against Swedish, a Providence affiliate, alleging that the hospital system not only failed to notify patients they were eligible for charity care but also sent 54,000 patients to collections and “Train[ed] employees to aggressively collect payment without regard for a patient’s eligibility for financial assistance, instructing them to use a specific script when communicating with patients that gives patients the impression that they are expected to pay for their care. Providence instructed employees: “Don’t accept the first no.”’ The Attorney General subsequently amended the lawsuit to add state debt collection Act violations. The case remains pending.

While the Providence case is among the worst, it is certainly not the only one.

In June 2023, the New York Times reported that Allina Health System (yes, the same one identified earlier in this article for charging exorbitant interest on medical bills) systematically denied care for patients with unpaid bills (except services provided in the emergency department). Implementing this policy meant denying critical care to children and individuals with chronic conditions that need regular, ongoing treatment. The Minnesota Attorney General announced an investigation into Allina following the article’s publication; shortly after, Allina rescinded the policy. That is all well and good going forward but remember that this same nonprofit hospital system spent less than 1% of its operating revenue on charity care from 2018 until 2021. In 2020, at the height of the pandemic, the health system collected an estimated $209 million from tax exemptions in excess of charity care delivered.

An investigation by the KFF Health News found that more than two-thirds of hospitals sue patients or take other adversarial action against patients with unpaid medical bills. Further, an analysis by the Lown Institute, in its 2023 Results Fair Share Spending: How Much are Hospitals Giving Back to their Communities, estimated that, in 2020, nonprofit hospitals had a total deficit of charity care of over $14 billion. That is a lot of zeros, amounting to missed opportunities to deliver on what used to be the undisputed mission of the community hospital.

And I’ve seen it before…And I’ll see it again…*

Hospitals contend that charity care is not the total of what is included in the community benefit and point to other investments that benefit the community. While it is true that charity care is not all that community benefit includes, it is, without question, a central part of it. It is also a concrete, measurable output, the impact and actual benefit of which is established and desperately needed. The same cannot be said of all other community benefit activities. A 2018 study by researchers at Johns Hopkins evaluating the cost and benefit of current nonprofit hospital operations concluded that “some” of the eight other categories that the IRS list as qualifying as a “community benefit” actually confer direct, additional benefits to the hospital and may more fairly be considered marketing efforts or otherwise be self-serving for the hospital. For example, some nonprofit hospitals cite mobile health clinics, which enable access to healthcare for patients who otherwise lack access or would have to travel long distances to receive healthcare. However, this generally remains a commercial or revenue-generating activity. It just makes good business sense: meet your consumer where they are. The patients (or the insurance payer, including Medicaid and Medicare) pay for the care rendered and the hospital benefits by establishing a referral source for patients needing hospital-based care and services. It is a good business practice where the community benefit is ancillary to the underlying objective: growing the business.

And, so, we are back here again. We have debated the community benefit standard application – and its enforcement since 1969. That’s more than 50 years. Is the community benefit standard too vague? Yes. Is there insufficient oversight by the IRS? Yes. As the GAO concluded a few years ago in its report, Tax Administration: Opportunities Exist to Improve Oversight of Hospitals’ Tax-Exempt Status. Regardless of whether it is the chicken or the egg (or the fox guarding the hen house), the idea of basing a hospital’s nonprofit status on a general “community benefit” continues to trip up a fair, objective, and consistent evaluation of the substantial public subsidies conferred on these enterprises. And that needs to change.

It is time that we acknowledge (after fifty years) that a “community benefit” is not an accurate description of what we expect (or should expect) from nonprofit entities. After all, most economic activities confer community benefits. But are those “community benefits” drivers of the entity’s actions – or merely an ancillary output? We don’t wish to undervalue a community hospital’s importance on its community’s economic health, stability, and employment opportunities. But the same can be said of any similar-sized private, for-profit enterprise – and at much less public expense. For example, for-profit hospitals in communities also provide sizable investments in “community benefits,” including providing charity care.

Finally, in addition to defining and enforcing our expectations of what a nonprofit hospital should do (or, rather, must do), we should also reflect on what they should not do. They should not hound individuals for payment of services they know or should know do not have the ability to pay. Just think back to the data from the Federal Consumer Protection Bureau (see Figure 1), households hold most individuals with medical debt in collection with an annual income of $40,0000 or less, and many of these households have children. At a minimum, nonprofit hospitals do not have sufficient screening processes to identify and enroll individuals eligible for financial assistance, which must be resolved. Every patient should be screened for financial assistance eligibility and granted such status at the time of care. Furthermore, once a debt is incurred, nonprofit hospitals should never engage in punitive debt collection practices against individuals who do not have the ability to pay, regardless of the procedural steps that the hospital takes before pursuing these actions. This includes wage garnishment, body attachment, and imposition of interest. While we speak of the community benefit justifying nonprofit hospitals’ privileged tax status, we also must keep in mind the individual and collective harm created by many hospitals’ billing operations. Because, let us be honest: this is not a case of a few health systems engaging in practices that (as Senators Grassley, Warnock, and Cassidy diplomatically framed it) are “not in the best interest of the patient”- these practices are prevalent across the industry which actively harms individuals and the stability and prosperity of the community. That can’t be ignored.

But let’s keep it simple. Perhaps it is time to get really clear and specific: nonprofit hospitals must provide charity care equal to an established percentage of their tax exemption (federal, state, and local), and they must fully account for it on the 990 and other tax reporting documents. It doesn’t need to be any more complicated than that.

* Acknowledgement: History Repeating (Knee Length Mix) [feat. Shirley Bassey] Propellerheads, Decksandrumsandrockandroll 20th Anniversary.