If, like me, you were born between the years 1977 and 1983 (or when the original Star Wars trilogy was released), you might be an “Xennial.”

Hold on, a what?

You heard me right. A “Xennial.” It’s a new term for the micro-generation that is stuck smack dab in the middle of two significant generations in American history: Generation X and Millennials. We got cell phones later in life, used dial-up modems to do school research, made mix tapes for crushes and, of course, played the Oregon Trail.

It has been said that Xennials experienced an analogue childhood and a digital adulthood. Technology has had a huge impact on our lives in a way that is unique from the generations that bookend us. We have adapted easily to technological advances, but are not as bound to them as our juniors. As such, we are in a unique position to help bridge the generational gap that currently exists by finding ways to utilize technology innovations that improve life while still paying homage to the past.

I, personally, have played this role in many aspects of my life both at home and in the workplace. At home, this role has taken the form of (trying) to teach my young boys the value of achieving success without having to default to technology for the quick answer. They constantly refer to my childhood as “the olden days” and, while this term conjures the image of covered wagons and butter churns for me, they consider anything pre-smart phones as essentially living in the stone ages!

As a consultant in the health care industry, I have also worked on countless projects and initiatives where I have used my knowledge and experience in policy and operations to bridge the gap between the “lifers” who hold a wealth of institutional knowledge and the “disruptors” who seek to innovate and integrate technology that increases efficiency and instills value.

These experiences have taught me that good communication is paramount when bringing people with varying perspectives together. We must be ready to listen and capable of sharing information to find success in these situations. To achieve this, we must be “speaking the same language” or we run the risk of talking past, not with, one another no matter how open we are to hearing. This is especially true when dealing with complex topics such as technology and health care.

A foundational step of good communication is to develop a common vocabulary with clearly defined terms. This will ensure that all parties can participate in the discussion.

So with that in mind, I would like to take this opportunity as an Xennial and an experienced “translator” of health care policy to write an ongoing series on the trending innovation of technology in health care. With the advent of stay-at-home orders and socially distancing due to COVID-19 the utilization of telehealth has gone through the roof. FAIR Health reports that private insurance telehealth claims increased by over 8000% in April 2020 (from 0.1% to 13% of claims) over the previous year. And nearly half (43.5%) of Medicare patients saw their primary caregiver via a telehealth visit in April as compared to 0.1% in February. While telehealth utilization slowed some between April and May of this year, experts believe telehealth is here to stay. And with the recent Executive Order from the Trump administration to expand access to telehealth benefits permanently, we agree this is a trend to watch.

So today, I’m beginning with common definitions for all the terms you are hearing used out there. And later on, we can dive into some of the other interesting and innovative happenings in telehealth, like how government agencies and payers are further refining definitions to regulate what is reimbursable as a telehealth visit or service.

TELEHEALTH VS. TELEMEDICINE

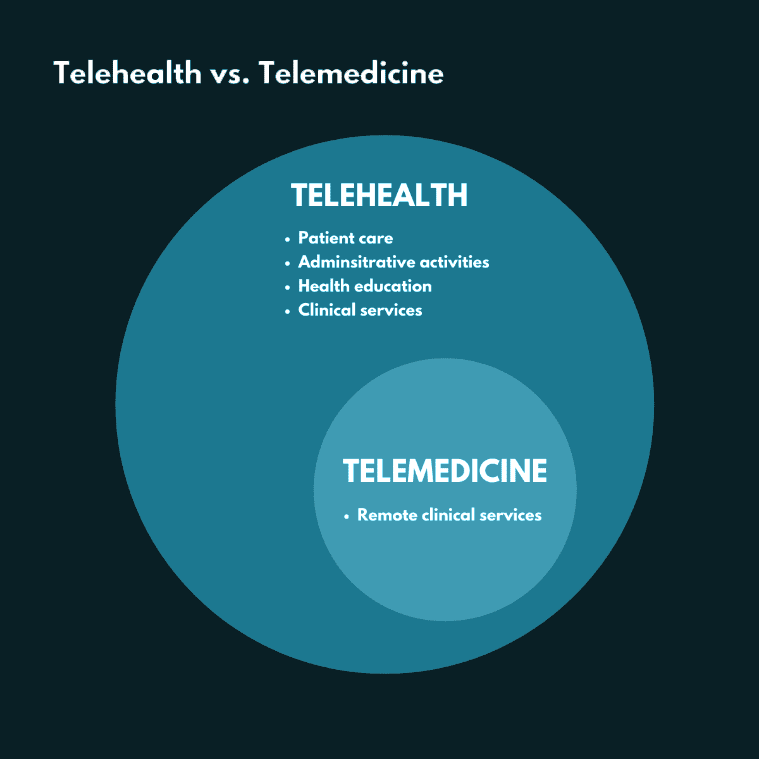

Although the terms telemedicine and telehealth are often used interchangeably, there is actually an important distinction between the two. Telehealth is different from telemedicine in that it refers to a broader scope of remote health-related services than telemedicine alone.

According to the Center for Connected Health Policy, telehealth is the use of telecommunications technologies to deliver health-related services and information that support patient care, administrative activities, and health education.) Examples of telehealth, provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), include care coordination, provider-to-provider interactions, education, and public health.

Telemedicine, on the other hand, is defined by the American Telemedicine Association (ATA) as when medical information is exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s clinical health status.

MODALITIES

Under the umbrella term telehealth, four additional terms are used that focus on the modality of technology that is leveraged to provide services and supports that address health-related needs. You may be familiar with these terms if you are a parent of school-age children living through COVID-19: synchronous and asynchronous.

Synchronous communications require the presence of both parties at the same time and a communication link between them that allows a real-time interaction to take place. These include “virtual visits” that take place between patients and clinicians via communications technology. Video and audio connectivity allows virtual meetings to occur in real-time, from essentially any location.

Asynchronous communications or “store and forward” as it is sometimes referred, is collecting clinical information and sending it electronically to another site for evaluation. This information typically includes demographic data, medical history, documents such as laboratory reports, and image, video and/or sound files.

Two other modalities to be familiar with include:

Remote patient monitoring (RPM): Technology that uses devices to remotely collect and send data to a home health agency or a remote diagnostic testing facility for interpretation. Such applications are particularly useful for individuals with chronic conditions who need continuous monitoring and might include a specific vital sign, such as blood glucose or heart ECG, or a variety of indicators for homebound consumers.

Mobile health (mHealth) is an emerging mode of care that includes the monitoring and sharing of health information via mobile technology such as wearables (Apple Watch, Fitbit, etc.) and health tracking apps.

There are many other terms being used to refer to telehealth uses within specialty areas such as telepsychiatry, telepharmacy, e-consults, etc. These all fall under the umbrella of telehealth and utilize one of the four modalities described above. However, as this field continues to rapidly evolve, we are seeing new technologies that utilize multiple modalities to facilitate the provision of care within a single application. As such, federal and state administrators (Medicare and Medicaid) and commercial payers will need to continuously assess and revise reimbursement criteria to keep up with innovations in the marketplace. And they are not alone, no matter what your generational affiliation, you as a savvy consumer and/or provider of healthcare need to also be in the know because let’s face it life as we know it has changed, and in this socially distanced world technology is going to keep us connected. So we will address these issues and others in upcoming articles and work to keep you up to speed on the ever-changing landscape of telehealth by directing you to important resources that can help your organization adopt innovations and adapt to changes in this new environment.