Last week Congress passed the much-anticipated American Rescue Plan of 2021 (“ARP”). This $1.9 trillion bill represents the third relief bill during the COVID-19 Public health emergency, as well as the largest single economic relief legislation in American history.

It isn’t just the size of the investment (although there is that) that is garnering attention and comparison to FDR and LBJ—the scope of the legislation is also impressive. There is hardly a component of the social services framework that is not directly impacted by this legislation: from extended unemployment benefits and expanded food stamps and nutritional services assistance, to financial aid to cover back rent and mortgages and enhanced child tax credits and investment in public health infrastructure. The ARP is not just a pandemic response and economic stimulus package—it is a significant, signature piece of anti-poverty legislation. As Andre Perry, Senior Fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, noted: “We haven’t seen a shift like this since FDR…..It’s a recognition that the social safety net is not working and was not working prior to the pandemic.”

Of course, here at Atrómitos, we are particularly interested in the impact of the ARP on health care and there are numerous direct and indirect intersections that merit evaluation. The ARP represents the biggest piece of health legislation (with the biggest impact to insurance coverage) since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) a decade before. Indeed, as we will discuss in the following sections, the legislation harkens back to the ACA, seeking to build upon its foundations and correct missteps or lost opportunities identified following its passage. This, most notably, includes closing the marketplace premium subsidies “gap” and adding more “carrots” to encourage states to expand Medicaid.

PUBLIC HEALTH FUNDING: PRESENT NEEDS AND FUTURE INVESTMENT

There are many lessons to draw from our experience over the past year. The importance of funding a resilient and interoperable public health infrastructure leads my personal list. In recent decades, our public health institutions have faced chronic and accelerated underfunding resulting in a “hollowing out” of the infrastructure and networks necessary to combat the crisis. Unless addressed and corrected, that is a problem that is going to persist long after the last vaccine is administered.

The ARP, like the previous COVID-19 relief acts, appropriates funds for continued COVID-19 testing and tracking, as well as for the administration and distribution of the vaccine in response to the pandemic. However, this legislation goes beyond the immediate needs created by the pandemic and clearly has an eye towards reconstituting our public health network, with particular attention to public health workforce capacity development and technological investments. An additional $7.66 billion is earmarked for state, local, and territorial public health departments to fund staffing, technology, and other needs necessary to support broad public health efforts.

ACA MARKETPLACE SUBSIDIES

The legislation does four things as it relates to the ACA marketplace subsidies available to individuals. Briefly, it:

- Removes the maximum income cap, extending subsidies to people with income above 400% of the Federal Poverty Line who would not otherwise qualify for subsidies. Anyone whose premium payments constitute over 8.5% of their income is now eligible for a premium tax credit on a sliding scale;

- Increases the subsidies available to low-income individuals who already qualify for the subsidies;

- “Forgives” over-payment of subsidies paid in 2020 based on misestimation of income. This means that people who received tax credits in 2020 who would otherwise have to pay back the subsidy in 2021 when their income overshot their estimate will not be subject to any repayment; and,

- Encourages state’s continued investment in “marketplace modernizations”–allocating $20 million dollars to subsidize state’s updates to portals and systems.

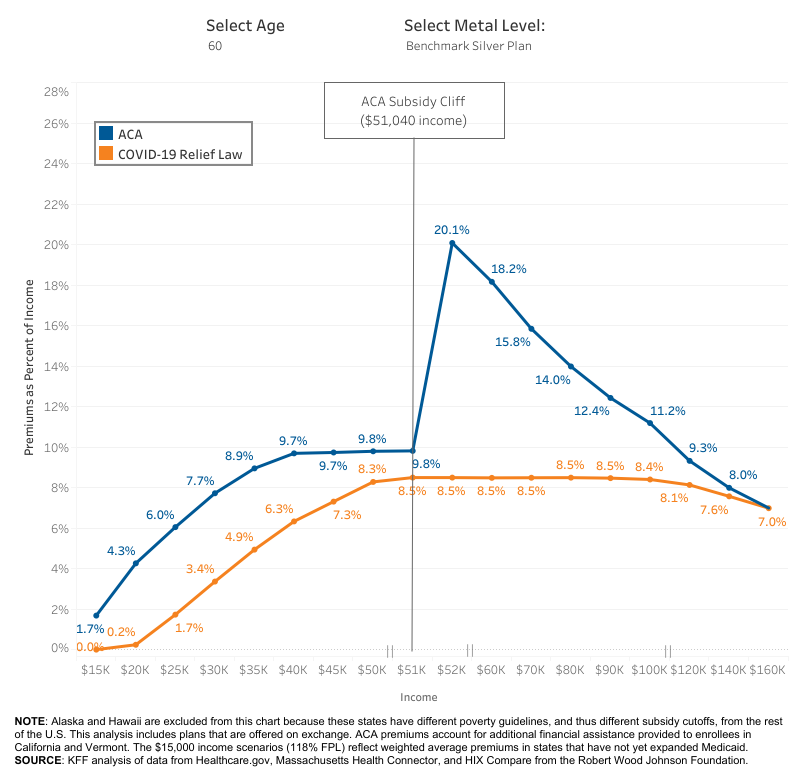

These extensions and enhancements of individual subsidies to ACA marketplace insurance premiums are time-limited and will expire in 2022. The removal of the income cap for premium tax credits represents perhaps the most significant modification, flattening what was previously described as the “subsidy cliff.” The “subsidy cliff” describes individuals just above the cut-off line ($51,400 for an individual) who, on average, paid more than twice in premiums than those receiving federal subsidies. The helpful graph below from the Kaiser Family Foundation represents this incongruity and the burden placed on individuals immediately above the eligibility line.

Modification of eligibility for (and the generosity of) these subsidies is expected to extend coverage to previously uninsured individuals by an additional 800,000 people in 2021 and 1.3 million in 2022, per an analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.

ADDITIONAL RELIEF FOR RURAL HEALTH PROVIDERS

The Pandemic has deepened an existing rural health care crisis. Through the ARP, Congress provided two avenues for direct relief to rural healthcare providers. The first is through the institution of targeted funds within the (existing) Provider Relief Fund and the second is through grants that will be administered through the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act created the Provider Relief Fund to reimburse providers (specifically hospitals and other facilities) for COVID-19-related expenses and lost revenues. In no small part owing to the urgency and depth of the crisis, Congress provided little guidance as to the distribution of the $175 billion across providers.

In this go-round, Congress took a more targeted approach. Instead of supplementing this general fund, the ARP allocated $8.5 billion to the creation of a separate program specifically targeting rural providers serving Medicaid and Medicare recipients. Distributions are subject to formal application and review—again indicating a more structured evaluation of need compared to previous relief interventions.

The legislation also allocated $500 million to be dispersed by the USDA to qualifying entities (including local governments and non-profit organizations) through grants for the coverage of not only COVID-19 related expenses and other operational capacity needs but also for the purposes of investing in telehealth infrastructure and capacity development.

MORE “CARROTS” TO ENCOURAGE MEDICAID EXPANSION

The ARP further encourages states who have not expanded Medicaid to reconsider expansion, offering a 5% increase in federal coverage of costs. For background, under the ACA, the federal government assumed 100% of the costs for expanded populations within a state up until 2016, after which point the federal share “phased down” to 90%, and states then bearing 10% of the cost of covering expanded populations thereafter. The ARP thus provides 95% coverage of the costs of covering expanded populations (adults with income up to 138% of the federal poverty line) for the next two years.

IN SUM

The ARP is a “colossus” of a bill and this quick evaluation is by no means comprehensive of the full intersection of health issues confronted in the legislation. To do that, this article might read more like the rapidly scrolling disclaimer on a pharmaceutical ad.

But as we wrap up, some other aspects of the ARP to keep in mind are that it:

- Mandates Medicaid’s coverage (without cost-sharing) for treatment and prevention of COVID-19 throughout the course of the public health emergency;

- Provides $350 billion to states, local governments, and tribes which may be used to make investments in public health infrastructure and capacity development, as well as to fill the shortfall created by lost revenue (and increased need) from the emergency;

- Allocates $3 billion for grants to states and local government for outreach and treatment related to mental health and substance abuse disorders;

- Permits states to (voluntarily) extend Medicaid/CHIP coverage to women for up to 12 months after the birth of a child (this is otherwise limited to 2 months after birth);

- Subsidizes COBRA coverage through September 2021.

It is also clear that this legislation is a beginning point – and not an end. We, here at Atrómitos, will continue to watch with avid interest.