Change in healthcare is often slow and incremental (and that is putting it politely). But there are moments in history, like the current COVID crisis, that can have transformational effects on the system.

Today, we bring you a care delivery innovation—the Hospital-at-Home model—that, if broadly embraced, can have a significant positive impact on the delivery system. But before we dive into the ins and outs of the model, it’s important to first understand how the hospital industry in the United States came to be and how COVID has forced stakeholders to re-examine assumptions about how, when, and where care can be delivered. We will then review the key aspects of the Hospital-at-Home model and where this specific approach falls in the continuum of home-based care initiatives. And, because money talks, we will provide an overview of programmatic requirements that must be followed to receive waiver approval and reimbursement under the CMS Acute Hospital-at-Home program. Finally, this article will highlight the benefits of the program and important considerations that may impact the future sustainability of the program.

A BRIEF HISTORY ON THE GROWTH OF THE HOSPITAL INDUSTRY IN THE U.S.

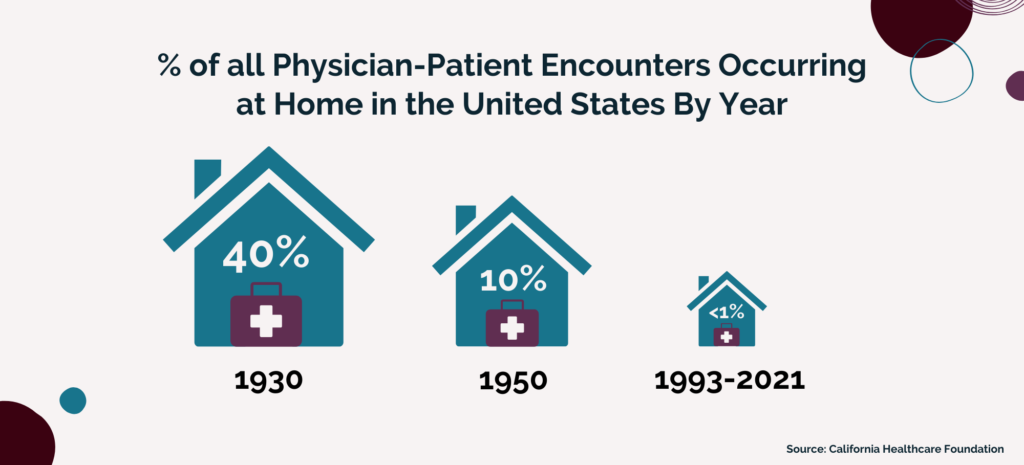

Medical care delivered in the home used to be a central part, and expectation, of American medicine. For some of you, it may conjure up images of the Country Doctor making house calls with his trusty black leather medical bag in hand. Indeed, the home visit was standard practice in the 1930s comprising 40% of all physician-patient encounters in the United States.

Fast-forward twenty years to 1950 at which point only 10% of medical interactions occurred in the home. Fast-forward again to 1993 and less than 1% of all Medicare physician visits occur at home, a figure which is still true today. While many factors likely played a role in this decline, one can point to the growing dominance of hospitals—first as a national, public health strategy, and then as a self-sustained industry—in the U.S. as the primary driver of this change.

A surge of demand for health care (and investment in health care infrastructure) occurred after World War II, causing the government to step in and contribute large sums of money to fund hospital enterprises. The establishment of the Hill-Burton Act of 1946[i] provided federal funding for the expansion of hospitals. The Act funded construction grants and loans to communities with a need (population size) that would be sustainable (per capita income). In return, they agreed to provide a reasonable volume of services to people unable to pay and to make their services available to all persons residing in the facility’s area. By 1975, the Hill-Burton Act had funded the construction of nearly one-third of all U.S. hospitals. That year the Act was rolled into bigger legislation known as the Public Health Service Act and by the turn of the century, about 6,800 facilities in 4,000 communities had been, in some part, financed by the Act. These facilities included not only hospitals and clinics but also rehabilitation centers and long-term care facilities.

Equally important to the expansion of hospitals was the development of expensive medical diagnostics and treatment approaches that involved large capital expenditures and the industrialization of health care more generally. Again, the federal government played a significant role by funding the expansion of the National Institutes of Health in the 1950s and 60s which in turn stimulated both for-profit and non-profit research. Furthermore, the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 provided money for the care of the aged and the poor, respectively.

The direction of the American hospital has shifted radically over time. The past three decades have seen a myriad of shifts in hospital ownership, control, and configuration—with the most recent trend being towards consolidation of the industry. In fact, over the past decade there have been more than 680 hospital mergers. This wave of consolidation—which is ongoing and likely to accelerate in the coming years—is characterized both by mergers between hospital systems and by large hospital conglomerates taking over rural hospitals, physician offices, ambulatory surgical centers, and other outpatient clinics (for further analysis on this trend, check out our earlier article: “The Cost of Consolidation”). Today, about two-thirds of the nation’s 5,000 hospitals are parts of for-profit chains—up from about half of hospitals just 15 years ago. And the share of for-profit hospitals has also steadily climbed with more than one in five hospitals now owned by investors, rather than being run as a not-for-profit or by the government.

While this movement toward larger organizations that provide an increasingly broad range of services has blurred the distinctions between types of health care organizations, one thing is certain: The hospital remains paramount.

CRISES PROPELS CHANGE: COVID, COST-CONTROL, AND VALUE-BASED CARE ENCOURAGES RE-EVALUATION

But there is nothing in life so certain as change. With the consistent (and alarming) rise in the cost of care over the past forty years, there has been increased recognition that the hospital—the centerpiece of the American health infrastructure—is not always the most efficient, effective, or equitable place to deliver care.

The movement towards value-based care—and the realignment of incentives to encourage more cost-effective and patient-centered delivery care—has made some headway in changing how we think about care delivery. More recently, over the past year, the COVID pandemic has shed light on the glaring deficits across our health care system including, but not limited to, hospital capacity, rural access, and medical supply chains. It has also forced health systems, providers, and other stakeholders to re-examine assumptions about how, when, and where care can be delivered. Concerns about possible surges of COVID-19 patients—combined with the spread of value-based payment and companies offering technology and operational support—have prompted health systems and health plans to view the Hospital-at-Home model as a solution to an immediate problem.

INTRODUCING THE “HOSPITAL-AT-HOME” MODEL

The Hospital-at-Home Model offers people the option of receiving acute-level care in their homes for certain ailments that would typically require hospitalization such as acute pneumonia or dehydration, or exacerbations of conditions like heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Use of this model, therefore, frees up beds in hospitals that can be used to treat COVID patients and provides non-COVID patients with a safer place to recover.

The first Hospital-at-Home program was developed in the United States 20 years ago by a team of geriatricians and health services researchers at Johns Hopkins University. The program was developed on the premise that hospitals were often not the best place to be treated and recover, given the risks of infection and the debilitating impact that hospital stays can have on patients who are frail, have cognitive impairments, or have other vulnerabilities.

Although the Model is one of the most studied health care delivery reforms, it has struggled to gain traction throughout the U.S., in part because Medicare’s fee-for-service program would not pay for its services. In recent years, a handful of U.S. health systems have launched similar programs, either because their hospitals are operating at capacity and/or they’ve taken on financial risk for their patients’ total cost of care and, thus, benefit from delivering services in a lower-cost setting. In these cases, payment is often coming from the health system’s Medicare Advantage health plan.

Over the past 30 years, a variety of home-based medical care models have been developed and implemented to address important gaps in health care delivery. These models span the home- and community-based care continuum and deliver a broad spectrum of services including primary care, urgent care, acute hospital care, and post-acute care. Some models provide longitudinal care (continuous over an extended period of time), while other models provide episodic care (primarily confined to a single incidence or time-limited episode of care over days to weeks). The Hospital-at-Home Model seeks to address the episodic needs of individuals with a hospital-level of care. To secure Medicare payment, hospitals must follow CMS requirements; however, there are some variations in the model among hospitals that have operated pre-COVID programs.

The evaluation process—which often occurs in the emergency department or ambulatory care—begins with healthcare staff identifying eligible patients using validated criteria.[ii] Eligible patients are evaluated by the physician who will oversee their home-based care and are then transported home by ambulance.

The patients receive extended nursing care during the initial portion of their “admission,” which then tapers off to daily nursing visits based on clinical need. A physician will also visit the patient daily for an evaluation and will implement any necessary diagnostic measures or treatments at home. Such measures can include electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, X-rays, oxygen therapy, and intravenous fluids or antibiotics. For some procedures such as MRIs and endoscopies, patients need to make a brief trip to the hospital.

The rapid expansion of telehealth technologies such as remote patient monitoring, enhanced video visits, and automation has enhanced the reach of this program—enabling required daily evaluations to be conducted remotely by registered nurses and physicians.

This care process continues until the patient is stable and, at the time of discharge, care reverts to the patient’s primary care physician and (most often) a home-based care agency that can provide the necessary level of care in the home.

OVERVIEW OF CMS WAIVER REQUIREMENTS

In March 2020, CMS announced the Hospitals Without Walls program, a program that would provide broad regulatory flexibility allowing hospitals to treat patients in locations outside of the hospital, including their homes. In November 2020, CMS expanded the initiative with the Acute Hospital Care at Home program, allowing hospitals to treat patients requiring acute inpatient admission in locations outside of the hospital, including their homes.

The program clearly differentiates the delivery of acute hospital care at home from more traditional home health services. While home health care provides important skilled nursing and other skilled care services, Acute Hospital Care at Home (CMS’ official name for the model) is for beneficiaries who require acute inpatient admission to a hospital and at least daily rounding by a physician and a medical team monitoring their care needs on an ongoing basis.

Under the Acute Hospital Care at Home program, CMS’ approval waives §482.23(b) and (b)(1) of the Hospital Conditions of Participation, which require nursing services to be provided on-premises 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and the immediate availability of a registered nurse for the care of any patient.

To participate in CMS’s initiative, hospitals must apply for a designated waiver via an online portal, with existing Hospital-at-Home operators eligible for “an expedited process.” To obtain approval, participating hospitals will need to demonstrate their ability to conduct:

- Appropriate medical and non-medical screening protocols;

- An in-person physician evaluation before starting care in the home;

- Daily evaluation of each patient by a physician or advanced practice provider either in person or remotely;

- Daily evaluation of each patient by a registered nurse either in person or remotely;

- Two in-person visits daily by either a registered nurse or mobile integrated health paramedics;

- Immediate, on-demand remote audio connection with an Acute Hospital Care at Home team member who can immediately connect either an RN or MD to the patient;

- Response to a decompensating patient within 30 minutes;

- Tracking on several patient safety metrics with weekly or monthly reporting, depending on the hospital’s prior experience level;

- Local safety committee to review patient safety data;

- Patient leveling process to ensure that only patients requiring an acute level of care are treated; and,

- Other services required during an inpatient hospitalization.

To monitor the program, CMS will collect data (i.e., patient volumes, unanticipated mortality rates, escalation rates, and more) from participants.

As of April 16, 56 health systems and 127 hospitals across 29 states have been accepted as participants in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Hospital-at-Home initiative, which is officially dubbed the “Acute Hospital Care at Home” program.

BENEFITS OF THE HOSPITAL-AT-HOME MODEL

The benefits of the Model go well beyond relieving the current hospital bed capacity issues related to COVID. As far back as 2005, the Model proved to be beneficial to patients, providers, and payers alike. Johns Hopkins’ first national study of the model found patients treated via the Hospital-at-Home Model had:

- Better clinical outcomes;

- A shorter average length of stay (3.2 days versus 4.9 days);

- Higher patient and family satisfaction;

- Fewer lab and diagnostic tests compared to similar hospitalized patients;

- Fewer complications often associated with hospital stays, such as delirium, infections, and the need for sedative medications or physical restraints; and,

- Lower care costs by up to 30 percent compared to traditional inpatient care.

Today, many patients have reported satisfaction with the Model because of its convenience and comfort in receiving care in their own homes. The model also allows caregivers or family members to remain at the patient’s bedside, which is not always possible in hospitals today due to COVID-19 visitor restrictions.

For hospitals, the Model can translate into greater cost savings and more clinical efficiency. The Model also offers unique benefits during the pandemic, including conservation of personal protective equipment, greater bed availability, and the ability to keep infectious patients out of the hospital.

FUTURE OF THE MODEL: BEYOND COVID

Payment Needed. The temporary nature of the CMS waivers and payment mechanisms will remain a barrier to widespread adoption of this model. Experts like Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform and former advisor on the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC)[iii], argue for the permanency of the model. In an interview with the Commonwealth Fund, he said the following:

“The pandemic made it clear that we need that kind of capability. The model has already been used successfully in many places, so it doesn’t need more testing or evaluation through the Innovation Center. CMS and other payers should simply start paying for it. If any problems develop, we can make adjustments just like we do with every other payment system, but there is no reason to continue denying patients the ability to receive care in this desirable and cost-effective way.”

Partners Needed. Health systems and hospitals are driving this process, but they are not experts in home-based care and will likely need to engage outside expertise in this area to develop operational protocols to ensure the success of the program. For Hospital-at-Home to work, hospitals and home-based care providers need each other. Just as there are elements of providing care in the home that evade hospital staff, there are specific clinical capabilities that home health agencies must develop. Skilled home care is not the same as hospital level of care; the patients are much sicker, and that is an adjustment for home health agencies. Presumably, non-medical home care providers also can play important roles in Hospital-at-Home models, especially as health care providers better begin to understand the connection between social determinants of health and staying out of the hospital.

IN CONCLUSION

The Hospital-at-Home model represents a care delivery innovation that is both a radical departure from the assumptions and strategy of over seventy years of American Health policy, but is also firmly rooted in previous delivery models and expectations.

Here at Atrómitos, we strive to ensure that our work reflects a singular common mission: Creating healthier, more resilient, and more equitable communities. Working toward this shared goal requires innovation and cross-sectional collaboration across the healthcare system. As healthcare policy experts, we can contribute to this effort by highlighting care delivery innovations (like the Hospital-at-Home model) that improve outcomes for our communities and reduce the cost of care. Expanding upon our Telehealth series, we will continue to keep you abreast of these care delivery innovations in the hopes that providers, payers, and policy-makers can take action to implement them in your communities.

[i] Titles VI and XVI of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC §§ 291 – PDF and 300) require health facilities that received certain Federal funds (“Hill-Burton” funds) to provide certain services to members of its designated community 42 CFR 124, Subpart G.

[ii] There are 60 acute conditions eligible under the program, including but not limited to heart failure, asthma, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Evaluations are conducted to determine whether the condition can be safely managed from their home with proper monitoring and treatment protocols.

[iii] The committee was created by Congress in 2015 to evaluate physicians’ ideas for new Medicare payment models and recommend promising ones to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In recent years, PTAC recommended that HHS implement two hospital-at-home programs that demonstrated patients given acute services in their own homes had fewer complications and accrued lower costs than similar patients treated in a hospital.